Though I’ve heard ballet dancers say there are moments onstage when they feel more like actors than athletes, I’ve always assumed the choices available to dancers as actors were few, and that embodying a character was secondary to embodying the most perfect lines of one’s own body. Under ballet’s demands of technical precision, I thought character could only emerge within a confined menu of available steps and techniques, like a plant growing in a controlled lab.

Article continues after advertisement

But when the dancer Aran Bell, in his role as Romeo, found Juliet’s lifeless body in the crypt, I finally understood. I was high up in my own balcony, in the cheap seats, but could see each muscle of his face tremble. He crumpled over his lover’s body, heaving with a depth of grief that let his dancing access his character’s centuries-old pain.

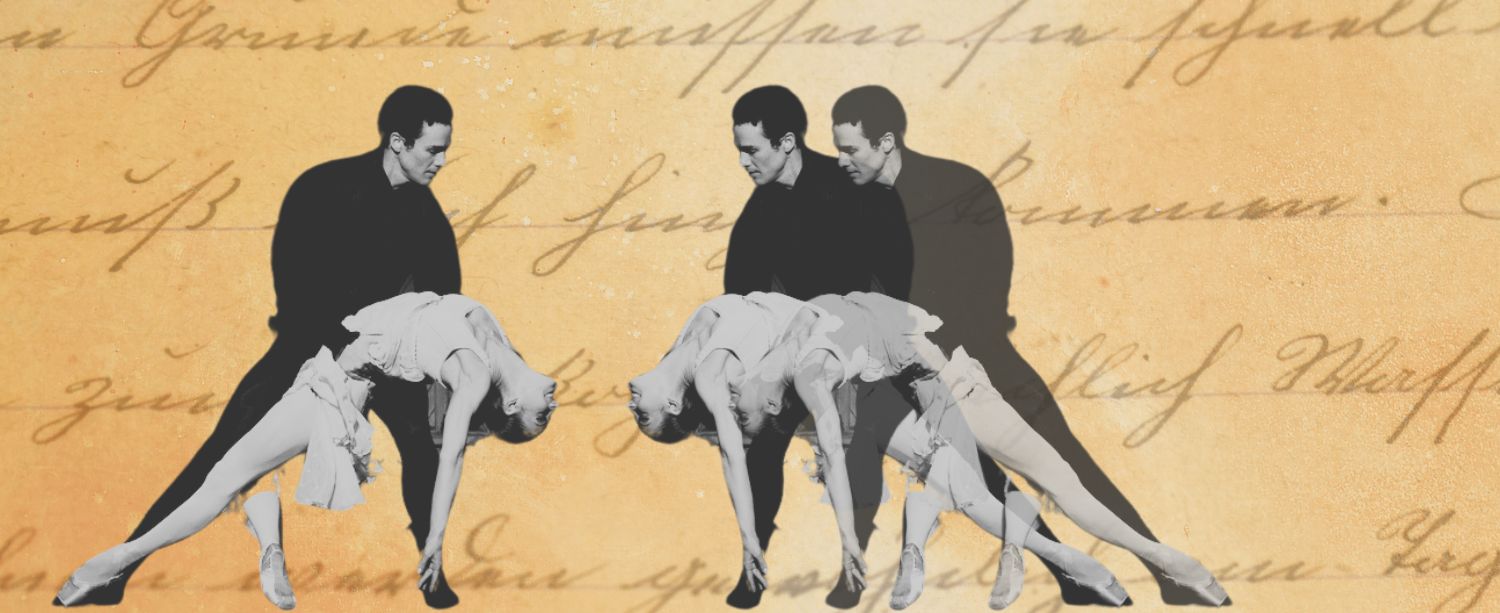

And when Christine Shevchenko, as the heroine Tatyana, emerged onstage in the final act of Onegin with her aristocratic husband. The lines of her lithe body were made even straighter now by pride and class ascension. Shevchenko spun victoriously through her St. Petersburg palace as if squashing her past provincial self like a bug beneath her toe box.

And when Daniel Camargo and SunMi Park, as the long-repressed lovers in Like Water for Chocolate, embraced after being forced apart for over twenty years. The lifts that Camargo held Park through weren’t the gentle and effortless arabesque lifts of polite characters; they were the hungry thrashings of desperate ones.

Throughout June and July, I watched American Ballet Theatre (ABT)’s New York City programming adapt literature to dance. I watched through antique opera glasses, and when I came back up for air, my eyes ached from looking through their magnification for too long. I wanted to drink every turn, every touch, every glint of eye contact.

Mostly, I studied dancers and their infinite individual planes of feeling. I followed the lines of characters as they flitted sleeplessly, tiptoed like children, reeled from shame, rebelled and transformed. I’d fixate on a dancer for so long that I’d miss a sequence in another wing of the stage or forget to drink in the profound symmetry of the full corps in formation. In the transformation of literature to performance, a story ceases to be something that I can control by holding it between my hands. But part of the pleasure of this season’s literary ballets was in the effort it takes to experience something fleeting—in the straining to see.

Ballet critics sometimes draw a line between story ballets—called staid in their use of rigid techniques to replicate traditional romantic arcs—and contemporary ballets that subvert classic molds with choreographic risk-taking and emphasize emotional gesturing over linear narrative. But the binary between narrative and non-narrative ballets feels to me like an unhelpful one. My experience of this season’s productions, old and new, complicated that distinction: the most traditionally story-bound productions proved just as capable of surprising me and holding intense grief, love, joy, and loss.

Maybe my eyes just insisted on seeing every balletic rebirth as a beautiful one. I felt closest to this season’s characters in their vulnerable and fumbling moments of transition, through class statuses and illnesses and coming of age and the thickets of love affairs. These in-between moments made them feel more kindred to the awkwardness and sensitivity of literary characters than to the perfection I once associated with ballet. Characters’ complicated psyches followed them as choreographers translated their lives to dance. If I squinted hard enough at the stage, I thought maybe I could glimpse their past lives in literature layered over their choreography, like looking at double-exposed film.

Many of this season’s source texts are only accessible to me through translated versions, where characters’ existence has already been negotiated by different cultural contexts and deepened or obfuscated through their transition from another language into English. At least forty-five writers and scholars have translated Alexander Pushkin’s Russian masterwork Eugene Onegin to English, wrestling with its poetic structure and context-specific cultural references and deeming it ultimately “untranslatable.” For a Russian speaker, Pushkin’s verses are carbonated by iambic tetrameter. The lines buoy between feminine and masculine rhymes, and the final two lines of each stanza land with crisp, symmetrical AA rhymes like a dancer’s feet landing on stage after she’s taken flight. Pushkin is cherished by Russian readers for his sonic innovations, which are inseparable from his materials (the Russian language) and which no translation could perfectly imitate with the materials of English.

The binary between narrative and non-narrative ballets feels to me like an unhelpful one. This season’s productions complicated that distinction: the most traditionally story-bound productions proved just as capable of surprising me and holding intense grief, love, joy, and loss.

Choreography makes “untranslatability” feel more like possibility. In the case of Onegin, John Cranko’s choreography uses the poetry of the human body to summon the parts of Pushkin’s novel that were deemed untranslatable—its commitments to rhythm, cadence, symmetry. In one particular scene from Pushkin’s novel, Tatyana (spelled “Tatiana” in American Ballet Theatre’s programming) has a turbulent night of dreams after meeting the cold and disinterested Onegin at her family’s home. She dreams that an avalanche of snow barrels towards her on a bridge, and when the snowbank shifts out of the way, a big, matted bear appears from beneath the white. The bear growls and rears its claws at her, and chases her through a forest where jagged branches yank off her earrings, scarf, and slippers. She’s saved in the dream by Onegin, who opens the door to a shelter and then fights off the hordes of cackling, hellish monsters that still await her. Onegin’s voice bursts into the fighting: “She’s mine!” In her dreams, Tatyana needs Onegin to protect her, and needs to believe he’d be the one saving, not the one harming.

The choreographer Cranko distilled Tatyana’s terrorizing by bears and monsters to the raw desire beneath the terror: her need to be claimed by Onegin as his. He reimagined the nightmare sequence as a romantic pas de deux, where Onegin materializes through the mirror in Tatyana’s bedroom. He takes her hand, glides her gracefully through space, and turns her delicately from a tour de promenade into effervescent pirouettes like she’s balancing on the head of a pin. She collapses into his chest, as if trust-falling into his outstretched arms. He presses her into vaulting overhead lifts—her head thrown back, her body arched, her legs dangling in front of his face. It’s the only scene in the ballet when Tatyana’s and Onegin’s desires intersect. Watching the principals Christine Shevchenko and Cory Stearns perform this duet in June, I could almost hear the whispers of trust and protection in their conversation of movement.

There are no monsters and bears who dance in Tatyana’s bedroom, but the adaptation to choreography feels faithful to Pushkin’s intentions in a more spiritual way. It’s as if the choreography sifts the novel’s elaborate nightmare through a fine mesh sieve and works with the small particles that remain: the essential pieces of longing and desire. The inaccessible words that hold me at a distance from Pushkin’s story disappear here, right in front of me, dissolved by the heat of the dancers’ bodies. At the end of the scene, Onegin walks back through the mirror portal he emerged from, leaving Tatyana feverishly dreaming. Their meeting—and the captive audience’s witnessing of their story—can’t last.

Another ballet this season, Like Water for Chocolate, finds a new balletic language for a story that has already been reshaped by translation. Laura Esquivel’s magical realist novel Como agua para chocolate was brought to English readers by the translators Carol and Thomas Christensen in 1992. Tita De la Garza, the protagonist, is cursed as the youngest daughter of her family: forbidden from marrying her true love Pedro and destined to care for her mother until the cruel matriarch passes away. Magical realism manifests in Tita’s alchemical homemaking. Her quail in rose petal sauce is an aphrodisiac so strong that it stops an army in its tracks. Her sorrow is so profound that it induces a mass episode of vomiting among everyone who ate the cake—for Pedro’s wedding to Tita’s older sister—that Tita wept while preparing. Through years of losses, the preparation of food is both a vessel and an elixir for Tita’s grief.

Much of this magic isn’t wholly reproduced in the Christensens’ translation. In one scene written by Esquivel, Tita rabidly knits and weeps until dawn, completing, in just one night, a quilt that should otherwise take a whole year to knit. But in the Christensens’ version, Tita only works on the quilt until dawn. The sheer ferocity in her knitting of the quilt, and the feat of completing it, both disappear. By separating the story from Esquivel’s intentions, the translators brought it closer to English readers’ expectations: making Latin American traditions of magical realism easier to experience and to believe.

If the politics of translation make characters and stories familiar to me and my English-speaking world, then maybe ballet can make them deliciously unfamiliar again. I can’t learn to read every language, but I can climb the bewitching velvet staircase of the theater and enter the balcony like a hidden portal in the dark. I can submit to the ballet’s multisensory surprises, squint to read the language of choreography, and watch dancers conjugate it in heartrending emotional registers. I can tune into dog-eared stories at new frequencies.

While the expression of desires and fears through movement is primal—everyone who watches dance has a body of their own—it would be an oversimplification to call dance a universal language. Like any language, ballet is an alphabet of non-exhaustive steps and techniques that choreographers re-imagine in equivocal, elusive, surprising combinations. It’s something I have to work hard to engage with.

This season, I sometimes joined my friends Sasha and Polina in the audience. With their combined thirty years of ballet training, they’re closer to native speakers of the visual language onstage. It’s not just that their reading of technique—recognizing that one dancer was particularly sharp, or another struggled to land in fifth position—lets them articulate opinions about the success with which a story was told. It’s more like their fluency in the language of choreography constructs, for them, the story itself. When they notice that the choreographer of Like Water for Chocolate opted for a contemporary form of renversé, they see that the character Tita’s world is changing: at the brink of the twentieth century, new technology and new social norms arrive on her farm throughout the story, modernizing her family’s life along with the language she dances. In Onegin, when Polina or Sasha recognizes that the choreography morphs from provincial Russian folk dance in the first act to bourgeois French-influenced steps in the final act, they understand that Tatyana is rising in the ranks of society, dancing with more conventionally elegant techniques as she ascends to more sophisticated circles. Part of the pleasure of watching ballet as an observer but never-participant is turning to these friends at intermission to ask their thoughts. I feel a deeper communion with the characters and their choreography when it takes effort to name and describe them together.

Vladimir Nabokov, in his project of bringing his literary forefather Pushkin to the English-speaking world, rejected the idea that translating literature should create a frictionless experience for a reader. In response to the many artists before him who tried to recreate the essence of Pushkin’s poetry in English, Nabokov argued that recreating sound, rhyme, meter, or pleasure is the wrong goal for an English translator. He believed “the clumsiest literal translation is a thousand times more useful than the prettiest paraphrase” and that an exacting treatment of each original word choice—combined with extensive footnotes that describe Pushkin’s poetic choices—is the only true translation. He translated the novel’s famous first stanza word-for-word like a court transcript:

Moi dyadya samykh chestnykh pravil,______ My uncle has most honest principles:

Kogda ne v shutku zanemog,_____________when taken ill in earnest,

On uvazhat sebya zastavil______________he has made one respect him

I luchshe vydumat ne mog._____________ and nothing better could invent.

Ego primer drugim nauka…____________To others, his example is a lesson…

It’s hard for me to reconcile the English lines with the promises of pleasure that accompany the Russian text’s legacy. The English words catch in my jaw, and I trip over “and nothing better could invent,” a punchline alienated from its subject. Who or what couldn’t create anything better? The translation loses every dimension of its color and character. It also loses the irreverent sarcasm that allows the narrator to reach out and touch native readers like a hard pat on the shoulder: the narrator is saying his uncle earned respect from others only once he fell ill, making his sickness a clever ploy which others should learn from. The shared experience of Pushkin’s genius among those who’ve read him in Russian—who describe his language as explosive, rich, groundbreaking—hides from me in plain sight, like I’ve overheard an inside joke and embarrass myself by asking what it means.

But Nabokov’s philosophy challenges my impulse to recoil from the difficulty of his translated version. His study of Eugene Onegin is a clinical, baroque textbook drowned in footnotes that intentionally gives readers a project rather than a leisure experience. His methodology demands that I become his partner in trying to reconstruct Pushkin’s original poetic choices. It asks me to work hard to compare the literal English output with Nabokov’s annotations—to squint to see where Pushkin’s pulse lives at the intersection.

Dance has the capacity to expand and deepen my understanding of story—adapting a plot without sanitizing it. But in classical ballet, that hasn’t always been the case.

In the challenging moments of Pushkin’s text that other English translations might smooth over, Nabokov leans in, naming and describing the difficulty. When he encounters Pushkin’s use of the word toska, he annotates the reasons why it can’t be neatly folded into the fabric of English: “No single word in English renders all the shades of toska. At its deepest and most painful, it is a sensation of great spiritual anguish, often without any specific cause.” Its other shades of possible meaning include “a dull ache of the soul, a longing with nothing to long for, a sick pining, a vague restlessness, mental throes, yearning” and more quotidian sensations like nostalgia, lovesickness, or boredom. But Nabokov doesn’t think a word like toska renders the whole work untranslatable, just that it demands a deeper commitment to excavating the nooks and crannies of the word.

The ABT principal dancer Cory Stearns, who danced the role of Onegin on the night I saw the production, understood that his job included acting out these shades of meaning: holding all of Onegin’s pining, restlessness, and boredom in his dancing. In the production’s Playbill, Stearns describes riffing on his choreography when his character first meets Tatyana: “I do these pirouettes, and my hand goes to my head numerous times.” He makes a choice to give his pirouettes an aloof, arrogant edge, like someone playing with his hair while you try to hold a conversation with him. His performance approximates something like Nabokov’s call to action: a call to look closely and follow a character’s complicated psyche.

Dance has the capacity to expand and deepen my understanding of story—adapting a plot without sanitizing it. But in classical ballet, that hasn’t always been the case. Complex and messy characters have sometimes been flattened by choreography that funnels them into ballet’s available molds of pas de deux. These duets, typically choregraphed between heterosexual romantic leads, haven’t traditionally accommodated creating the same level of depth for relationships between characters who are friends or family (to say nothing about queer relationships).

This historical mold limits the possibilities for reimagining literature in dance, when so many of the thorniest and most interesting relationships in literature are non-romantic. In the text of Eugene Onegin, for example, surprising moments of tenderness exist in Onegin’s friendships with other men. In an English translation by James E. Falen (who sought to preserve the original rhyme scheme), Onegin’s friendship with the character Lensky is shaded with wry and earnest affection:

But Lensky, having no desire

For marriage bonds or wedding bell,

Had cordial hopes that he’d acquire

The chance to know Onegin well.

And so they met—like wave with mountain;

Like verse with prose, like flame with fountain:

Their natures distant and apart.

At first their differences of heart

Made meetings dull at one another’s;

But then their friendship grew, and soon

They’d meet on horse each afternoon,

And in the end were close as brothers.

Thus people—so it seems to me—

Become good friends from sheer ennui.

When I read this stanza, I paused at its gentle humor and human acuity, the men’s candid journey from irritation to intimacy breaking through the verse’s translation to English. The choreography of the ballet adaptation had none of this shy, reticent fraternal closeness; the most contact that the two men make with each other on stage is when they eventually fight to the death. I’m not saying this was an oversight on the choreographer’s part; John Cranko was intentional in his decision to re-envision the story through Tatyana’s eyes, and her character is given more agency and growth than Onegin’s character. But these choreographic choices have the same effect of altering a story by bringing it closer—more familiar—to an audience’s expectations. In this case, classical ballet constructs an expectation to follow a romantic arc that spotlights heroines and female dancers as pinnacles of beauty and desire.

When he adapted Like Water for Chocolate, one of British choreographer Christopher Wheeldon’s intentions was to challenge these traditions in service of the stories and relationships that don’t fit neatly into classical molds. In his choreography, the physical fighting between Tita and her mother Elena became one of the most captivating and wrenching scenes I saw this season, and it’s a duet that wouldn’t normally exist in the classical repertoire in the first place. While there’s plenty of fighting in ballet, it’s typically reserved for fatal duels between male rivals. It’s uncommon in ballet to choreograph the type of abject aggression between two women where, in Like Water for Chocolate, Mama Elena drags her daughter’s body down onto the stage and mimes beating her, the sound of her fists thundering through six tiers of a stunned audience.

This heart-stopping scene of violence is one of the ways Wheeldon tried to honor the complex DNA of Esquivel’s characters, working directly with Esquivel to build extensive profiles of the novel’s characters and Esquivel’s intentions, bypassing the secondary source of the English translation.

In the last scene of Like Water, the characters Pedro and Tita finally reunite in a duet that pushes the conventions of what a pas de deux can look like. Finally emancipated from the family obligations and abuses that held them apart, they’re free now to melt into each other like chocolate bars in warm hands. The beauty of that union is transcendent. At every turn, SunMi Park and Daniel Camargo (as Tita and Pedro) kindle and cradle each other’s dancing: on top of shoulders, draped over the nape of a neck, spun from the small of a back. The voice of the soprano Maria Brea beams through the orchestral pit like holy light. For the first time in the production, an operatic aria accompanies the score, a hymn shepherding the lovers home. Pas de deux translates to “step of two” or “dance for two.” Man and woman step together, and so do author and choreographer, collaborating across time and space.

In the English translation of this scene from the novel, Tita remembers a piece of wisdom from another man she had considered marrying during Pedro’s exile from her: “If a strong emotion suddenly lights all the candles we carry inside ourselves, it creates a brightness that shines far beyond our normal vision and then a splendid tunnel appears that shows us the way that we forgot when we were born and calls us to recover our lost divine origin.” The sentence grates a scrap of sandpaper against Laura Esquivel’s language. Adjectives kick and climb over each other, fighting to take up space and wring out the last word. But onstage, it’s as if the choreography distills and re-translates the magic and magnetism of Esquivel’s work. The dancers find the candle buried somewhere in the metaphor and nurture its flame.

In their final moments together, Tita and Pedro disappear behind a gauzy curtain. A towering special effects projection of fire and explosions, cast onto the stage, subsumes them in flames—the characters, now at the end of their lives, find eternity together in the afterlife. They’d nursed the flickering light, spun together in stronger and stronger tufts of air, and let the flame grow until the full blaze immortalized them. It’s the version of their lives that I’ll remember.

Christine Shevchenko and Cory Stearns in Onegin. Photo: Rosalie O’Connor, courtesy of American Ballet Theatre.