This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

Article continues after advertisement

Stream of consciousness is not a literary affectation as many like to think, but the way our brains naturally work; traditionally we’re taught that narrative fiction requires breaks and quotation marks and chapters to be accessible, that dense, unbroken novels with serpentine sentences and flights of fancy are a bit “literary” and “mannered.” But consider the way you tell a story and the conversations you have. You may be listening to a friend describe a new restaurant while you’re also thinking of the assignment at work you need to finish or why the forecast was for rain but there isn’t a cloud in the sky. This doesn’t make you a bad friend or a bad listener, it makes you human. Our brains have different trains of thoughts moving concurrently all of the time. All fiction is artifice, however a more conventional novel with its page breaks, chapter breaks and use of quotation marks often feels more contrived than a novel whose style traces the paths a mind naturally follows.

I adore digression. Frankly, when I’m writing I want the plot or the premise out of the way. Not because I’m “for” or “against” plot (an argument which seems to be trending these days on social media). But, more than anything, I care about language. I want the words to erupt, the sentences to flower and the ideas to go places I hadn’t expected. The story will always follow.

My novels always begin with a very straightforward premise. In Saint Sebastian’s Abyss the reader knows on the first page that an ex-friend has asked our narrator to visit them on their deathbed in Berlin. In my new novel – which relishes in digression – the reader knows in the first sentence what’s going on: the narrator’s wife has died, he’s mourning, but now he has the time to finish his life’s work, an essay about the French philosopher Montaigne. There, I did it. That’s out of the way. Now I can meander, I can explore the memories, relationships, and events that have occurred in the character’s life while likewise investigating what they’re thinking about now. With this the narrator comes alive for me, digressing perhaps about the decision a decade ago that led him to this moment, or the scent of bergamot in a cup of earl grey or anything really, as long as it feels authentic, relevant, and helps the story.

After finding my premise I’m liberated, I can discover what the story and the characters are trying to tell me. I may find myself along the shores of the Bosporus or shoveling coal in a train in Soviet Russia. These strands aren’t the primary focus of the story per se, but they support and reinforce the story. Much like the human mind, I can go backwards and forwards, and not merely for the sake of doing it, but to explore (along with our narrator) what they care about, what they want to say and how to say it.

More than anything, I care about language. I want the words to erupt, the sentences to flower and the ideas to go places I hadn’t expected. The story will always follow.

Digression is intuition and improvisation, it’s the storyteller trusting the story and having faith it will tell them where to go; conversely, a plot with a strict structure doesn’t often take these liberties, it’s usually the writer telling the story where to go. There’s nothing wrong with either approach and there’s also nothing wrong with a writer using a little bit of both. Patricia Highsmith, one of my favorite novelists, doesn’t digress. She doesn’t have the time. Highsmith has a strict, focused, angular story to tell and digressions would only slow and hinder the momentum; it would also change her style. The same holds true for Stefan Zweig, whose propulsive novellas would be unnatural with digression.

Digression is a natural part of storytelling. All of us do it, and more often than you might think. If you want to tell a funny incident about something that happened at a wedding, you might need to give the listener some context. To do this you back up and explain the main players and the baggage they carry, their grudges and loyalties, their tumultuous affairs. Simply put: in order to tell the main thrust of your story you need smaller supporting stories to give the incident at the wedding the significance it demands. No one reads Tristram Shandy for the plot or the ending. One reads these books for the diversions, the nesting dolls of smaller stories inside, the wild tangents that branch out and leave smoke trails like Roman candles, excursions which help serve the mosaic of the novel. In One Thousand and One Nights, our narrator’s survival literally hinges on digression. Digressing, getting lost, is just as important as knowing where you’re going.

Without digression Don Quixote would be a novella or even smaller, a pamphlet.

And who wants that?

__________________________

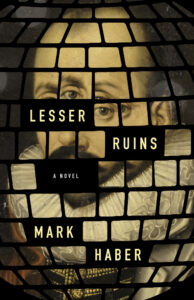

Lesser Ruins by Mark Haber is available now via Coffee House Press.