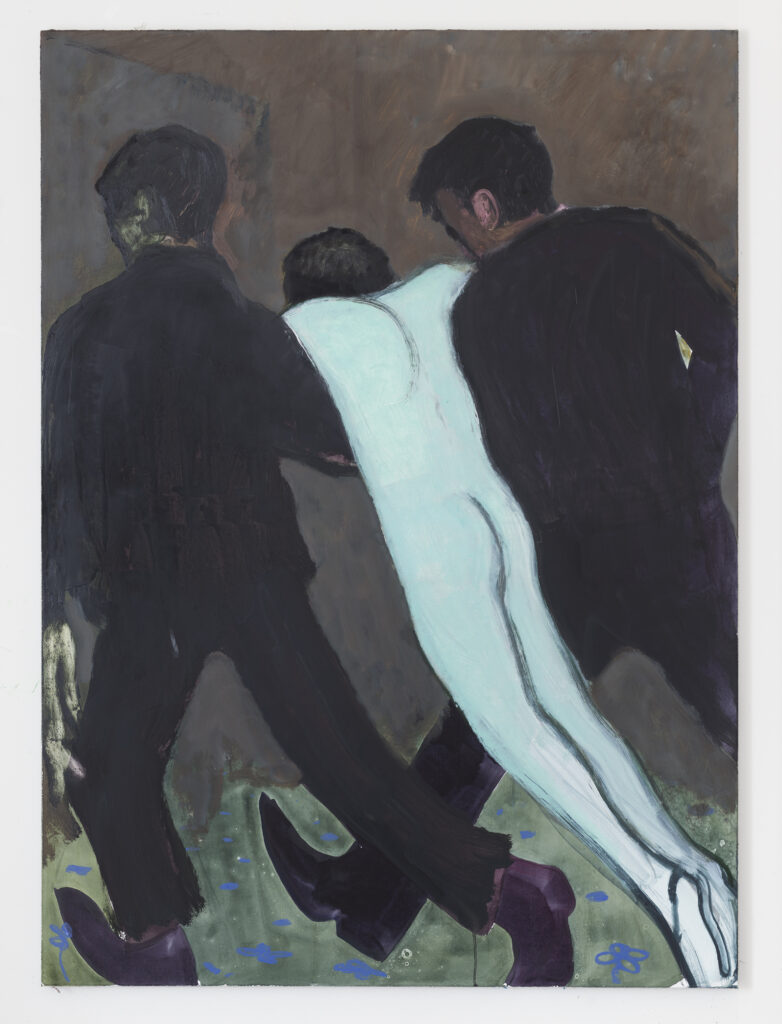

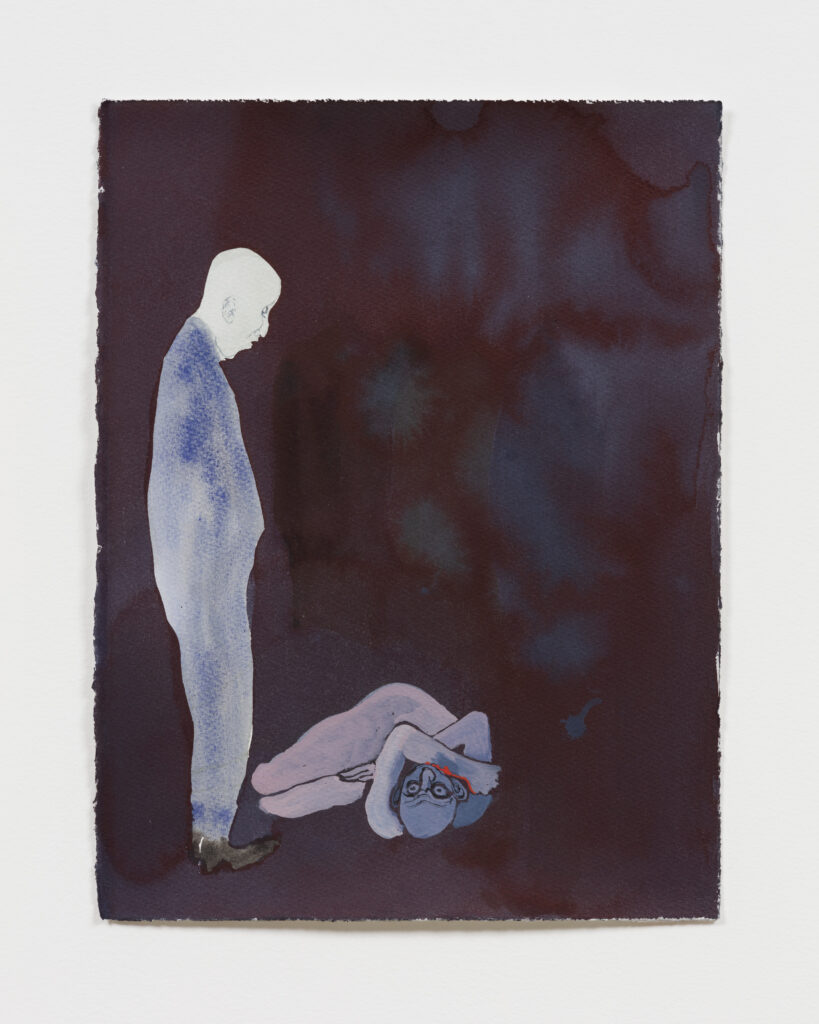

Saya Kantarovsky, Removal, 2018, oil and watercolor on linen, 55 ¼ x 40 ¼ in. Copyright the artist, courtesy the artist. Photograph by Adam Reich.

“A Child Is Being Beaten” is the strange title of Freud’s 1919 paper on sexual fantasy. This sentence, one of sadomasochistic, masturbatory enjoyment and announced from an unspecified source, indicates the phantasmatic scene admitted to by several of his patients. What are these beating fantasies? Freud says it is “not clearly sexual, not in itself sadistic, but yet the stuff from which both will later come.”

He’s trying to reach back to some primordial core of our subjectivity, centered on sexuality, the first outlines of guilt, and the desire for punishment. Also: the place where the prohibition against incest barely holds up in its commandment. The paper feels utterly wild—so many surprising elements are condensed into the phantasmatic image of an adult beating a child (usually a paternal representative, though sometimes the mother is present). Importantly, Freud notes, these aren’t the musings of perverse patients but rather the revelation of common daydreams—perhaps even unconscious universal scripts, that graft childhood experience with cultural mores.

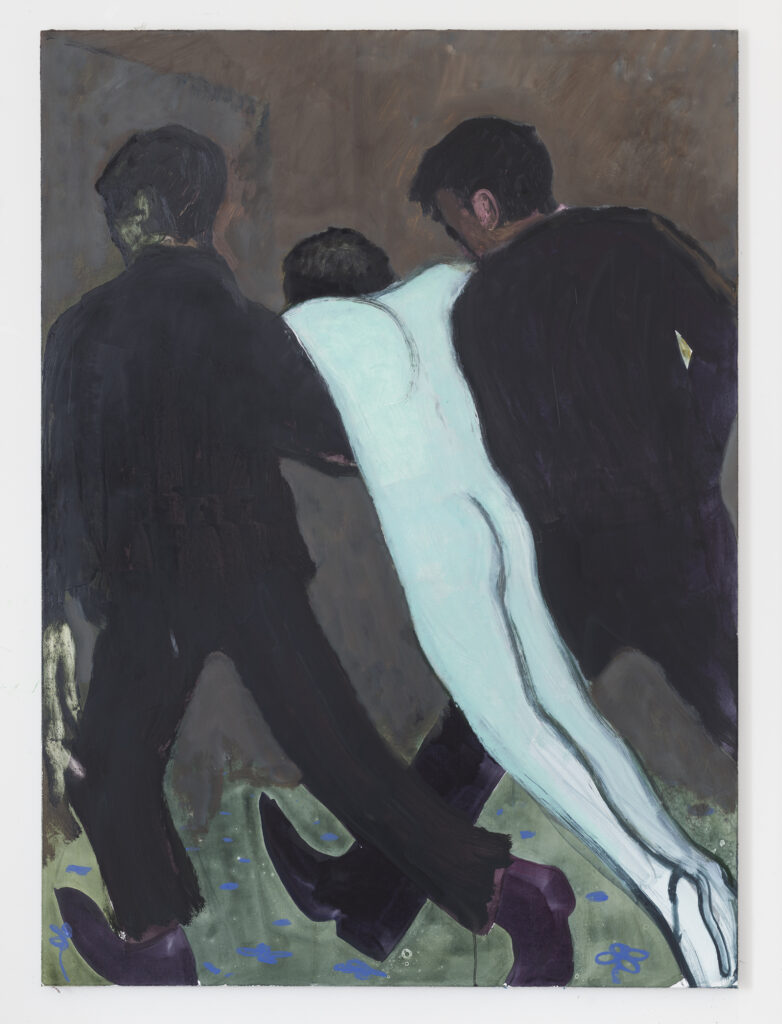

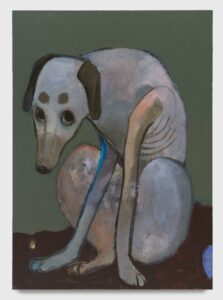

Emulsion, 2017, oil, watercolor, and pastel on canvas, 85 x 65 ⅛ in. Copyright the artist, courtesy the artist. Photograph by Robert Glowacki.

The fantasy is first a way of admitting sexual enjoyment, in tandem with the punishment and guilt one may feel for having it. There are also the outlines of a traumatic memory, according to Freud, of seeing other children punished, and wondering about this particular scene: What is loved and hated by these adults, what is good and what is bad—what, in essence, makes for authority? A potential identification with power is offered by the fantasy, the desire to be the one who beats, set against the one who is beaten. This impulse does the work of hiding a feeling of subjection, of utter helplessness; what we feel when our desire for another is so strong that we risk being harmed by them.

In the fantasy, we are everywhere and nowhere in the plot lines—the beater, the beaten, the voyeur. Such a diffusion of roles allows us to shirk responsibility for our manifold desires—pretend they aren’t our own, or that the other person simply wanted what we gave to them. Facing the pleasure or aggression of others dead-on is disconcerting, so the fantasy provides distance. It charts the multiplicity of places we occupy at any given moment, while we try to stay in our body, retain our feelings of excitement. Or don’t. Or, better, can’t. This was one of Freud’s earliest insights; as he states in The Interpretation of Dreams:

The fact that the dreamer’s own ego [ich] appears several times, or in several forms, in a dream is at bottom no more remarkable than that the ego [ich] should be contained in a conscious thought several times or in different places or connections—e.g. in the sentence “when I [ich] think what a healthy child I [ich] was.”

Freud reminds us that, to children, sex sounds like rhythmic beating, heavy breathing, scary moaning. Pregnancy and birth are likewise terrifyingly incomprehensible. Beating is not only the action of masturbation—beating off, and excitement’s periodicity as well—it is also a stand-in for the experience of insufficiency in the face of the reality of sex. Or in the face of all reality: the open face of wonderment in a child, versus the closed, supposedly knowing faces of adults.

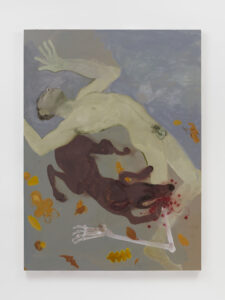

Annus Horribilis, 2020, oil and watercolor on linen, 102 ⅜ x 78 ¾ ins. Copyright the artist, courtesy the artist. Photograph by Pierre Le Hors.

“Beating” comes from Freud’s use of schlagen in German, which is an odd choice, because in addition to describing a violent blow, it also suggests the beats of music—more than other English words like hit, or strike. Freud seems to be telling us about how reality imprints itself on us, how it enters our senses—and also, how we absorb culture. It happens in beats, in blows, in morsels, fragments—never all at once, and rarely a complete process. He is drawing our attention to the linguistic, figurative, sensorial aspects of a life present in tonality, mood, aesthetic qualities—items that are meant to be felt and thus go beyond cognitive understanding. So beating is also about the way a body absorbs. In the realm of culture, this receiving has been tied to the father figure—one that is, and has always been, violent.

Breath, 2020. Oil and watercolor on linen. 74 ¾ x 55 ⅛ in. Copyright the artist, courtesy the artist. Photograph by Pierre Le Hors.

In typical Freudian fashion, we are getting closer to incest. How? Because incestuous wishes to merge with our parents, as well as visions of primal scenes, remind us of our separation from one another and the sheer fact of generational difference, even as we try to breach the boundary. A parent’s infanticidal wishes extend from a universal hatred for procreation (children are a reminder that we will die, as they will likely outlive us) and yet we procreate. This is why Freud constantly returns to the story of Oedipus Rex. It is a story of not only the love and hatred bound up in any given family, but also one of contradictory wishes rooted in the dawn of human life— a history that each of us still struggles with, and cannot escape.

In the beating fantasy, this imagined “sex,” as worthy of punishment, returns us to the sex that led to our own creation. It is a veritable existential breakdown. The fantasy is also then a scene of sheer narcissism, while paradoxically also a scene that explodes you—going where one was not and could not be, to a time before one was born—to this wrenching scene of one’s own conception.

According to psychoanalysis, we should be prohibited from getting too close to this place. Like the dream’s navel that touches an even greater unknown, Freud says, we locate the point where wishes rise like mushrooms from their mycelium. Don’t reach back too far! Hover around this point, but don’t believe you can crack the lock box. The narcissistic image—”I am the desired one, the chosen one being beaten”—must be struck down. It is not that we are beaten, or escape being beaten, we are everyone: victim, aggressor, onlooker, and worse, we are also beating ourselves.

Fighting with his disciples (who wanted to discover the beginnings of the unconscious), Freud argued that this movement backward was a move toward self-dissolution. It was an imagined return to the womb, a wish to find the origin of a world full of goodness (that doesn’t exist), like some kind of safe space where we are each the precious one, desired, sanctioned to live. All these imaginary topoi, before the caesura that drags us into the world, kicking and screaming.

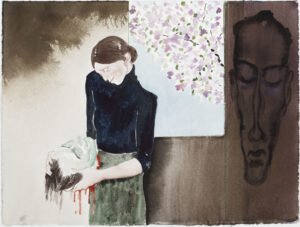

ASMR, 2020, watercolor and ink on Arches paper, 11 ¼ x 14 ¾ in. Copyright the Artist, courtesy the artist. Photograph by André Carvalho and Tugba

Carvalho – CHROMA.

Thus, the beating fantasy is also a fantasy of being born. Well, let’s not get ahead of ourselves. I’m a psychoanalyst. Everything reverts into its opposite—it’s also a fantasy of dying, of having been beaten to death. This was its more important underside for Freud. The difficult recognition of our mortality. I told you it was wild.

***

Why am I telling you about all this arcane psychoanalytic knowledge in a book about an artist? The story of Freud’s beating fantasies is also part of our tale, the origin story of Kantarovsky and myself. The first time we met, I had just finished speaking about masturbation fantasies in a lecture. His tone imparted a kind of urgency, and I took an interest in his work. And there it was: Kantarovsky as the boy being beaten, the boy beating himself, beating another—this whole phantasmagoria of negative pleasure upon which the minor joys, the ephemeral moments of happiness, rest. Sometimes that background needs to be placed in the foreground. More often, Freud said, what we call pleasure is in fact the removal of unpleasure. Sanya also told me that so many of his figures break the fourth wall, soliciting the viewer with a plea: Help me. One can’t help but think of the opening of Nathanael West’s Miss Lonelyhearts, letters that all say, Help me, “stamped from the dough of suffering with a heart-shaped cookie knife.” Or a heart-shaped painter’s brush …

This is what I put before you in my exegesis on Kantarovsky and beating fantasies: the improbable will to break yourself, your body, your mind, to locate this inkling of tenderness that is there, but always just out of reach or focus. All representation, all figuration, seems to collapse in on itself at this Archimedean point—what you say but can’t express, what you see but can’t perceive (or say you perceive), what you know but can’t really believe. Most are seduced by the idea of saying, seeing, knowing. It takes someone as suspicious and worn down to finally remove himself in the way Kantarovsky does in these works. As he said to me, “Everyone is trying to get out of their own way … but paradoxically, they’ve also already disappeared.”

How to stay with this painful stirring? In Freud, the artist always did this best, somehow working at the limit of repression while, as he said, keeping repression intact. They never know what they are doing. Kantarovsky always eschews knowing what he is up to. This isn’t a posture—at least when it’s this real. For Freud, artists work with what is painful in themselves, deriving satisfaction from it in the form of the final product, but rarely wanting to know with any clarity what the object they produce is about. Freud admired this doing-not-knowing. He said it must be the same for the true scientist. He considered this practice the epitome of what civilization can achieve beyond pure destruction.

Self Care, 2020, watercolor on Arches paper, 14 ¾ x 11 ¼ ins. Copyright the artist, courtesy the artist. Photograph by Pierre Le Hors.

One cannot get a sense for Kantarovsky’s paintings without understanding that they are on the hunt for this fragility. Also, that they are wild and speculative in the same way as Freud was in this paper—not only with their supposed content, but with paint, with brushstrokes, with materials as well. What appears to belong to individuals at their most grotesque, or desperate, or depraved—my masturbation fantasy, my neurosis, my pain—are shown as the only keys to the universe, best delivered to an audience through the complexity and negative consciousness of material mediums. As Angie Keefer wrote of Kantarovsky,

Kantarovsky’s paintings are good faith representations of bad, which demonstrate, paradoxically, that there is no such thing. That’s because bad faith constructs rely on oversimplifications, eliding difference and specificity to substitute one thing for another: a straw man for a disputant; a category for an individual. Therefore, bad faith representations tend to collapse under good faith consideration—i.e. scrutiny—that niggling executor of nuance, complexity, and specificity.

And it turns out that this universe is not so much made of our failing attempts to create categories and other species of judgment (to finally “appear”)—this would drag him into the world of narrative-based figurative painting—but rather, an effort that is reduced to materials, gestures, and sensation, and spills out into pigments, paint, watercolors, lacquer, splotches, erasures, and a whole prismatic array of colors.

Here, Kantarovsky can’t hold still. Unrelenting and almost attention-deficient, he must use everything in the history of painting at his disposal. He also does so with a demeanor opposite to his subject, painting with glee and optimism, with brazen exuberance.

***

A final word on melancholia. In 1917, a few years before Freud wrote “A Child Is Being Beaten,” he turned his attention to “Mourning and Melancholia.” The outlines of the beating fantasy appear there. Freud tries to understand that melancholic who berates himself, beats himself so adamantly, insisting on his worthlessness. “We see that the ego debases itself and rages against itself, and we understand as little as the patient what this can lead to and how it can change.” But, by looking at what mourning achieves, we might try to intuit what is taking place for the melancholic patient: namely, the acceptance of the loss of something or someone loved, an acknowledgment that they are deceased and need to be given up by an unconscious that refuses death. Freud writes,

Just as mourning impels the ego to give up the object by declaring the object to be dead and offering the ego the inducement of continuing to live, so does each single struggle of ambivalence loosen the fixation of the libido to the object by disparaging it, denigrating it and even as it were killing it. It is possible for the process in the Ucs. [unconscious] to come to an end, either after the fury has spent itself or after the object has been abandoned as valueless.

He notes that, between the two outcomes, it is not clear to him which is more successful or what they lead to. Though he acknowledges that, with the second, the ego might rejoice in an outcome that declares itself superior to the object given up. It’s another of those moments in which you see Freud smile wryly, because this renewed narcissism would set the foundations for another melancholic battle in the future. The expenditure (or draining) of rage then would be preferable. He says this without saying it.

In psychoanalysis, the most enigmatic, intense, and ambivalent battle around loss and separation is the one fought with the mother. Certainly, a kind of rage at the mother for what she couldn’t do or be for you; a rage that enlarges her as an image that must be taken apart, dismantled. As the psychoanalyst Adam Phillips has noted, the wish to be understood may be our most vengeful demand, “the way we hang on, as adults, to our grudge against our mothers; the way we never let them off the hook for not meeting our every need.” Only in reckoning with this universal melancholic rage against mothers can we perhaps locate new forms of tenderness—toward ourselves, but also toward women and children.

“A Child Is Being Beaten” was Freud’s next attempt to speak to this wish, this ambivalence, this violence, and this search. For what is beating if not also the rhythmic stroking of a mother? The necessity that she say no countless times, the longing for contact that can never fully be met, the feeling of an obstacle that was never a material one. Kantarovsky’s latest works are poised on this edge. It’s a world of mothers and small children, ghosts, intimate encounters, bodily embraces, endless longing, and fears that break not on the side of anxiety but of shame. Kantarovsky’s palate changes. There’s something even more internal to the works, as if we aren’t only inside the mind, but within a body.

Badgirl, 2023, oil on canvas, 15 ⅗ x 39 ½ in. Copyright the artist, courtesy the artist. Photograph by Jeffrey Sturges.

Huge portions of his canvases are now blank, monochromatic, or become dark spaces. He’s painting over something. Getting rid of it. Only leaving slight traces. Moving away. Separating himself even more strongly. The feeling is decidedly domestic, even when otherworldly. I feel as if I’m being brought into an uncanny space, which, as Freud noted, implies feeling not at home in something that is decidedly one’s home. He also said it must have to do with mothers, our original home. The image sequence of this monograph ends in this minimal space, with a gesture toward tenderness, the mother figure. Leaving behind the whip. Just a crack, nothing more. But you can almost smell her—as if the painterly materials he’s now exhausted change form, aerate, enter the senses differently. Not as a blow, but as a breath.

From Sanya Kantarovsky: Selected Works 2010–2024, to be published by MIT Press this month.

Jamieson Webster is a psychoanalyst and the author, most recently, of Disorganization and Sex and Conversion Disorder: Listening to the Body in Psychoanalysis. She is also the cowriter, with Simon Critchley, Stay, Illusion!: The Hamlet Doctrine. She teaches at the New School for Social Research.