[ad_1]

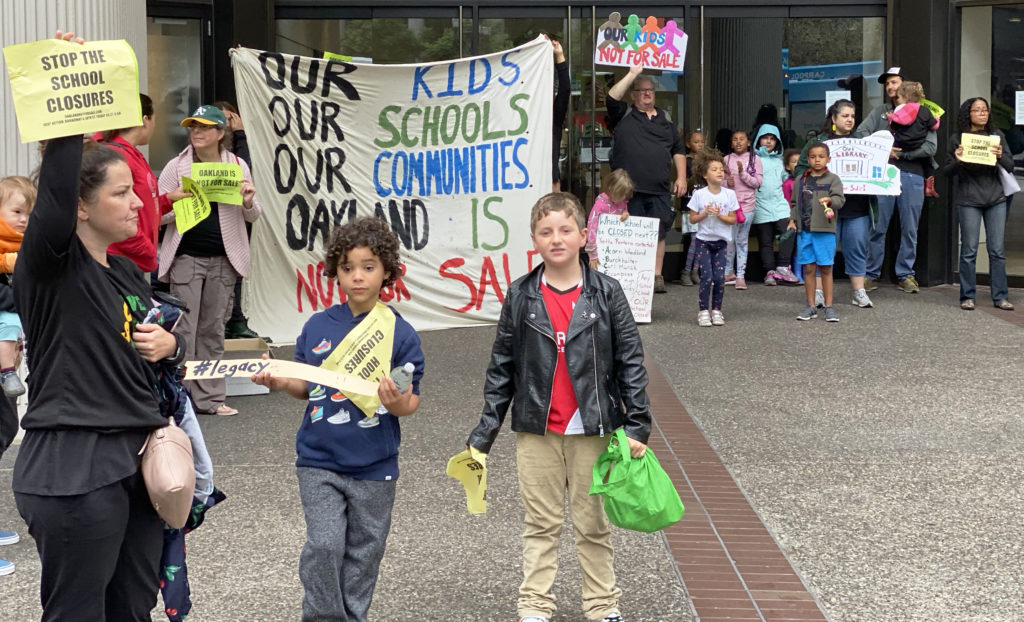

Protesters rally against school closures outside the Oakland Unified School District office in September 2019.

Andrew Reed/EdSource

As enrollments drop, city after city is facing pressure to close half-empty schools. Fewer kids means fewer dollars. Consolidating two schools saves money because it means paying for one less principal, librarian, nurse, PE teacher, counselor, reading coach, clerk, custodian … you get the idea. Low-enrollment schools end up on the chopping block because they’re the ones that typically cost more per pupil.

But there is another way to cut costs without closing underenrolled schools.

First, it’s worth noting that small schools needn’t cost more per pupil. Our school spending and outcomes data include examples of small schools all across the country that operate on per-pupil costs comparable to their larger peers — some even delivering solid student outcomes.

But here’s the catch: These financially viable small schools are staffed very differently than larger schools.

There’s a 55-student school near Yosemite that spends about $13,000 a student—well under the state average. How do they make it work? One teacher teaches grades two, three, and four. There’s no designated nurse, counselor, or PE teacher, and rather than offer traditional athletics, students learn to ski and hike.

A quick glance at the many different financially viable small schools across different states reveals that staff often wear multiple hats. The principal is also the Spanish teacher, or the counselor also teaches math.

Also common are multi-level classrooms. When my kids attended a small rural high school, physics was combined with AP Physics, which meant both my 10th and 12th graders were in the same class, but with different homework.

Sometimes schools give kids electives via online options, send students to other schools for sports, or forgo some of these services altogether. Some have no subs (merging classes in the case of an absence). Sometimes the schools partner with a community group or lean on parents to help in the library or coach sports.

Done well, smallness can be an asset, even with the more limited services and staff. Whereas a counselor might be critical in a larger school to ensure that a student has someone to talk to, with fewer students in a small school, relationships come easier. Teachers may have more bandwidth to assist a struggling student.

What isn’t financially viable? A school with the full complement of typical school staff but fewer kids. These aren’t purposely designed small schools, rather they’re underenrolled large schools (sometimes called “zombie schools”). Los Angeles Unified School District, for instance, has a slew of tiny schools spending over $30,000 per pupil. Such schools vary in performance, but all sustain their higher per-pupil price tag by drawing down funds meant for students in the rest of the district. In the end, no one wins.

With so much aversion from parents to closing schools (witness, for example, Seattle, Chicago, San Francisco, Oakland, Pittsburgh or Denver) we might expect more districts to adopt these nontraditional staffing models as a way to save costs and keep families happy.

In some cities, it’s the charter schools that are offering just that: smaller nontraditional programs that make it work without extra subsidies.

Some will argue that nontraditional schools (including charters) won’t work for every student. Districts must take all comers, including English learners, families needing extra supports, those wanting a full athletics program, specialty autism services, and so on. That said, the idea here is that larger districts needn’t offer those services in every school, provided they’re available elsewhere in the district.

But it’s these larger districts that are the most wedded to the uniform staffing structure. It’s so deeply embedded in job titles and union rules, as well as program specifications and more.

Tolerating small nontraditional schools would mean letting go of some of that rigidity and accepting the idea that schools can be successful without all those fixed inputs. And it might mean reducing some staff who believe their roles are protected when enshrined in a staffing formula. On the flip side, if the school in question has higher outcomes, and the choice is to close it or redesign its staffing structure to transform it into a more intentionally small school, parents and students may accept that trade if it means preserving the school community.

It would also mean changing budgeting practices so that what gets allocated is a fair share of the dollars per pupil—in contrast with allocations based on standardized staffing prescriptions.

The last decade saw a big push for inputs-based models, including “every school needs a counselor” or “every school needs a nurse.” As enrollments continue to fall, these inflexible one-size-fits-all allocations stand in the way of keeping small schools open.

None of this is to say that every school should remain open. Many will inevitably close. But for some of those that deliver solid outcomes for their students, perhaps now is the right time to rethink the typical schooling model.

This commentary was originally published by the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

•••

Marguerite Roza is Ddrector of the Edunomics Lab and research professor at Georgetown University, where she leads the McCourt School of Public Policy’s Certificate in Education Finance.

The opinions expressed in this commentary represent those of the author. EdSource welcomes commentaries representing diverse points of view. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us.

[ad_2]

Source link