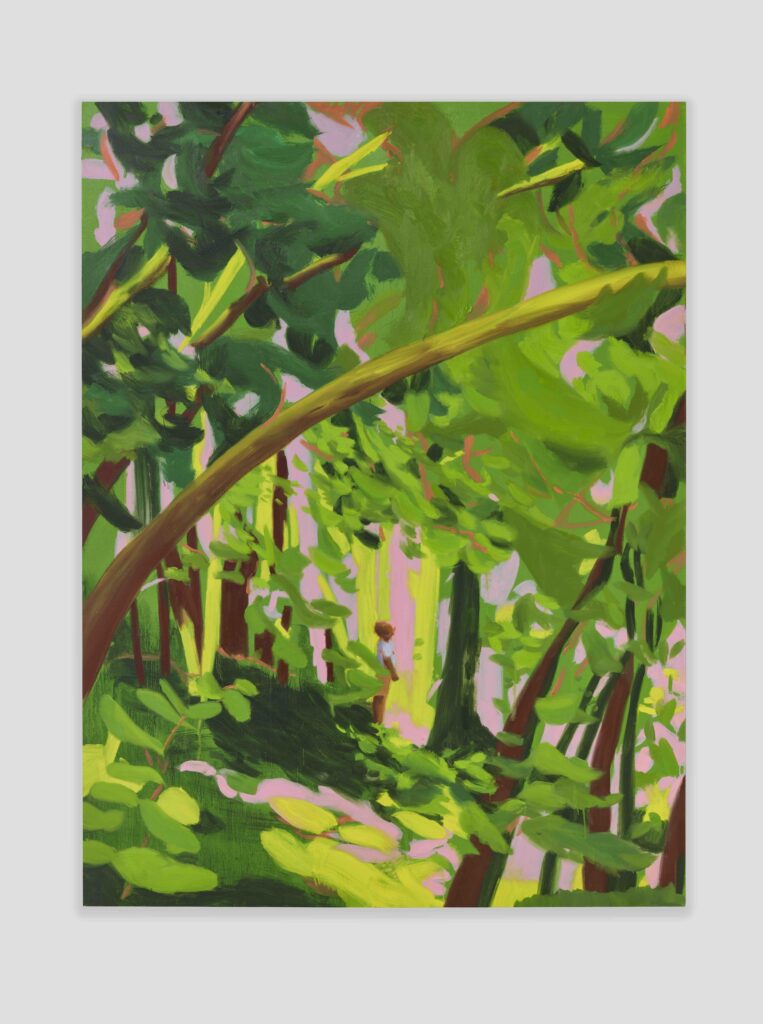

Nicole Wittenberg, Woods Walker 7 (2023–2024), oil on canvas, 96 x 72″.

Nicole Wittenberg has painted a variety of subjects over the last fifteen years, but two predominate: lush and lyrical landscapes, often of places where water meets land—generally unpopulated, but with an occasional figure glimpsed among the trees, as if to provide focus and scale—and her less well-known male nudes (along with an occasional pulchritudinous female counterpart), often engaged in sex acts that have seldom been depicted in Western high art. These pictures show sexual beings up close and personal, though maybe up close and impersonal is more to the point. They are exercises in concision and point of view; if you get close enough, anything looks big, and these dicks look monumental, like big trees in a low-rise landscape.

Despite their provocative, even polemical subject matter (why not paint dicks?) Wittenberg’s paintings of blowjobs and the form of self-care commonly known as jerking off are also concerned with style, with the how of painting as inseparable from the what. In paintings like Blow Job and Red Handed, Again, both from 2014, the how relies on a gesture that is high-risk and directionally sound. It is the precise placement along with a certain velocity that allows the gesture to adhere to the form. In terms of accuracy of brush mark, Wittenberg might be the Franz Kline of dick paintings. You have to paint something, and you may as well paint what interests you. Sometimes you might paint what interests others, to see if it also interests you. Are these paintings pornographic? I don’t know, maybe. I don’t really care—perhaps that descriptor is even a compliment. I’m not especially polemical in my approach to art or to life, but suffice it to say that the analytically sexual gaze in painting should be equally and unreservedly available to all. These are paintings that say, Oh, is this image making you uncomfortable? Get over it.

Nicole Wittenberg, Red Handed, Again, 2014, oil on canvas, 36 x 48″.

Wittenberg’s landscape paintings and pastels, on the other hand, belong to a long ancestral line; they derive, meanderingly, from some of the earliest paintings produced in this country, and they constitute a contemporary reframing of a potent and closely held self-image: the sense of wonder engendered by the pristine vastness of the North American landscape. It’s as F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote about the early Dutch settlers sailing into New Amsterdam, seeing for the first time the “fresh, green breast of the new world.”

Wittenberg posits two basic visions of this Arcadian heritage, the peopled and the unpeopled landscape, and both stem from her time living among the shallows and the depths of coastal Maine, where she has summered the last dozen or so years. One type of picture shows a densely wooded grove bordered by water, seen from the middle distance in the indistinct light of early morning or evening. In these seminocturnes, the landscape is shadowy and mysterious, more or less inaccessible—perhaps the view from a boat of one of the innumerable uninhabited islands that dot the Penobscot Bay, as in Cradle Cove (2022). Or the view from the shore as we contemplate a stand of trees halfway to the horizon in the fading pink light, as in After the Storm (2024). The illumination is dim; the trees are backlit and the colors of the woods and water as well as sky are all dark and close-valued. These pictures are portents of existential unease, of loneliness and something unresolved, and as such are a continuation of a soulful lineage; one feels Marsden Hartley standing behind them, and behind Hartley stands Albert Pinkham Ryder. Wittenberg’s luminous, unpeopled landscapes have a closely held, interior feeling of something that resists us, of an awareness just out of reach.

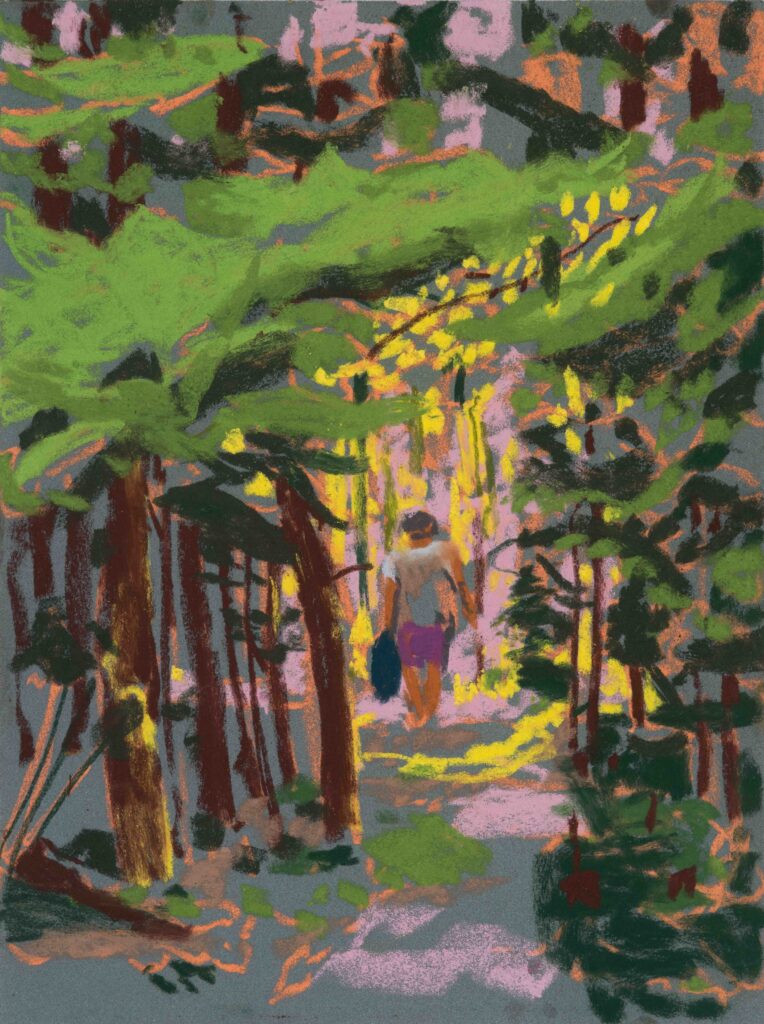

Nicole Wittenberg. Woods Walker (2021), pastel on paper, 15.5 x 11.5″.

The other type of landscape painting is also of the Maine woods but seen from within a grove of towering white pines. It is perhaps midday, the contrast between light and shadow is high, and a solitary figure wends his way beneath the swooping branches. These are the Woods Walker paintings, of which Wittenberg has painted a number of variations. The addition of the single figure marked a turning point in her art; we are inside the forest now, the figure is our surrogate, and though more of a participant in the passage of minutes and hours and the change in light, we are still vulnerable to the vicissitudes of nature, weather, and memory. The unspoken worry: Will we be able to find our way back? The ebullience one feels in that moment, walking in the brilliant light, arms swinging by one’s sides, may be short-lived.

Wittenberg’s paintings all share a concern for compression and for scale: dicks as big as trees and trees towering over diminutive hikers. Both are a function of point of view, which itself constitutes the painter’s first decisive act. The point of view goes a long way in setting a picture’s narrative capability. We only see what the painter chooses to show us; what is left out is not our concern. We can’t know what happens in the next instant, or after we stop looking. The mystery continues to unfold, with us or without us. This exact quality of light—hold it! In the next instant it changes, forever. The melancholy of painting.

David Salle’s essay “A Man Is Like a Tree” will appear in Nicole Wittenberg, the first survey of Wittenberg’s work, which will be published by Phaidon in July. The publication of the book coincides with two solo exhibitions of the artist’s work, at the Ogunquit Museum of American Art and the Center for Maine Contemporary Art.