For most of the last hundred years, statement architecture has played a central role at the Olympic and Paralympic Games. With that potentially set to change, we look back at 15 of the most significant examples as part of our Olympic Impact series.

Due to growing concerns about sustainability, far fewer permanent venues are likely to built for the Olympics in future.

At Paris 2024, the focus has been on using existing structures, with an understated timber aquatics centre the only major new stadium.

However, the games have commissioned numerous impressive works of architecture in their 128-year history.

Some of the world’s best known architects, including Pritzker Architecture Prize-winners Kenzo Tange, Jacques Herzog & Pierre de Meuron, Zaha Hadid and Frei Otto have designed venues for the games.

Beyond simply forming the backdrop for athletic endeavour, these buildings have often helped to define each Olympics.

Below are the 15 most architecturally significant Olympic buildings:

Olympic Stadium by Jan Wils, Amsterdam 1928

Designed by architect Jan Wils as the main venue for the 1928 Olympics, this red-brick stadium is a key example of the Amsterdam School architecture style – part of the wider international expressionist style.

Wils won an Olympic gold medal in the architecture competition for the design of the stadium as part of the art competitions that were included in the early games.

A 46-metre tower overlooking the stadium is topped with a cauldron that held the first Olympic flame.

Olympic Stadium by Werner March and Albert Speer, Berlin 1936

Designed by German architects Werner March and Albert Speer, the Olympiastadion in Berlin was commissioned by Adolf Hitler to be the centrepiece of the infamous 1936 Olympics.

The colossal stadium has an instantly recognisable form, with its seating bowl broken by a large gap where the Olympic torch was originally placed.

It has since hosted the 1974 and 2006 World Cups, as well as the recent final of the 2024 Euro football tournament.

Like Wils, March was himself a winner at the games, taking home an Olympic gold and silver medal for the design of the park surrounding the stadium.

Palazzetto dello Sport by Annibale Vitellozzi and Pier Luigi Nervi, Rome 1960

Designed by Italian architect Annibale Vitellozzi, the Palazzetto dello Sport basketball venue is topped with a 60-metre-diameter dome.

The thin reinforced-concrete roof, which was engineered by Pier Luigi Nervi, was created from 1,620 prefabricated pieces and supported on a ring of Y-shaped flying buttresses.

Nervi designed several other structures at the games including the nearby Flaminio Stadium, co-designed with his son Antonio Nervi, and the Corso di Francia Viaduct road bridge.

In the south of the city, the Palazzo dello Sport, co-designed with architect Marcello Piacentini, hosted the boxing events.

Yoyogi National Stadium by Kenzo Tange, Tokyo 1964

Designed by Pritzker Architecture Prize-winner Tange as the aquatics centre for Tokyo’s 1964 Games, the arena is topped with a distinctive, draped roof.

The highly engineered roof was hung from a pair of large steel cables hung from two concrete towers and anchored to the ground.

Following the games, the swimming pool was removed and the arena converted to be used for ice hockey, gymnastics, basketball and volleyball.

The stadium was one of several 1964 Olympics venues that were reused as venues during the 2020 games.

Nippon Budokan by Mamoru Yamada, Tokyo 1964

Also built for the 1964 Olympics, the octagonal Nippon Budokan was designed by Japanese architect Mamoru Yamada to host the judo events at the Games.

Like Yoyogi National Stadium, the venue was reused at the 2020 games, when it hosted the karate events.

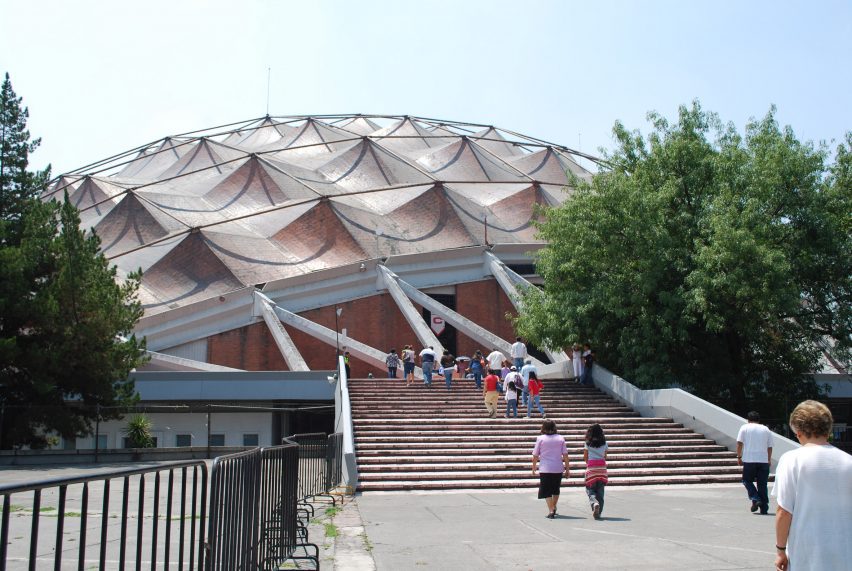

Palacio de los Deportes by Félix Candela, Mexico City 1968

Another Olympic building with a distinctive roof, the Palacio de los Deportes was built to host the basketball events at the Mexico City games.

Designed by Spanish-Mexican architect Félix Candela, who is known for the development of thin concrete shell roofs, the circular arena is topped with a square-patterned dome.

Made of copper-clad plywood sheets, this roof is supported on a tubular aluminium frame resting on steel arches.

Olympiapark by Behnisch & Partner and Frei Otto, Munich 1972

Perhaps the best-known project by Otto, who was posthumously awarded the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2015, the Olympiapark in Munich was the centrepiece of the 1972 Olympics.

German architecture studio Behnisch & Partner arranged the main venues – stadium, aquatics centre and gymnastics arena – alongside a lake at a former rubbish dump.

To unite the venues, they were all topped with a translucent canopy created by Otto, which was supported on 58 cast-steel pylons. The pioneering tensile structure was designed to echo the peaks of the nearby Alps mountains.

Olympic Stadium by Roger Taillibert, Montreal 1976

Nicknamed The Big O due to its doughnut-shaped roof, the main stadium for the Montreal Olympics was designed by French architect Roger Taillibert.

Its unique roof was designed to be retractable, using cables attached to a 165-metre-high inclined tower, which stands alongside the stadium and contains the games’ aquatic centre.

Due to construction delays the stadium’s roof and tower were not complete for the Olympics, with the project finally finished in 1987. Even when complete, the roof could not operate in high winds and in total was only ever raised 88 times.

Olympic Gymnastics Arena by Kim Swoo-geun and David H Geiger, Seoul 1988

This gymnastics arena was the most interesting building constructed for Seoul 1988.

Designed by architect Kim Swoo-geun with engineer David H Geiger, the building is topped with a self-supporting cable dome, which was the first of its kind.

A smaller venue topped with a similar roof was built alongside it to host the fencing events.

Montjuïc Communications Tower by Santiago Calatrava, Barcelona 1992

Despite not being a venue for events, the Montjuïc Communications Tower is one of the most recognisable structures created for the Barcelona Olympics.

Designed by Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava to transmit television coverage of the games, the 136-metre-tall structure is meant to evoke an athlete holding a torch.

Olympic Velodrome by Santiago Calatrava, Athens 2004

Calatrava designed numerous structures for the Athens Games as part of an overhaul of the Athens Olympic Sports Complex, designed to improve the quality of the venues while adding a unifying aesthetic.

He added roofs to the two largest venues on the site, the stadium and velodrome, both in his signature style.

At the velodrome, he enclosed the venue with a roof hung from cables supported on a pair of tubular steel arches, which echo the roof of the stadium. The roof was clad with wood internally to improve acoustics, while a central strip of glass provides natural light.

Along with the venues, Calatrava designed a series of 99 tubular steel arches that connect the venues and the kinetic Nations Wall sculpture, as well as entrance canopies, bus stops and other street furniture.

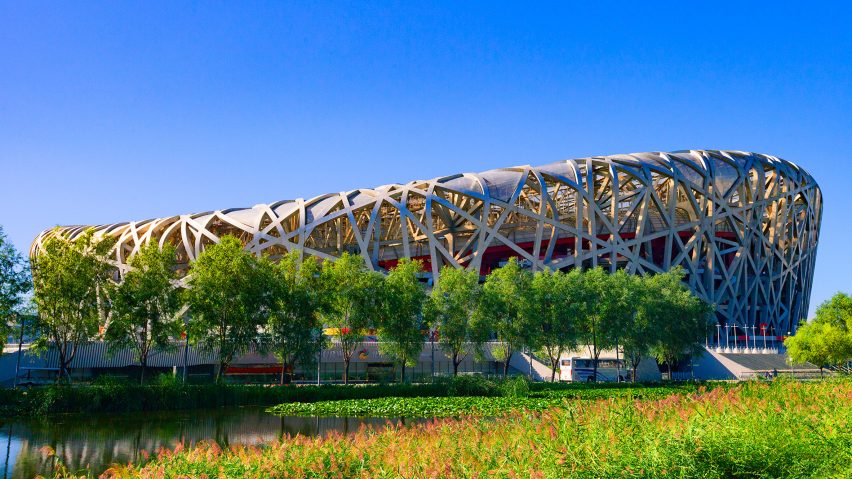

National Stadium by Herzog & de Meuron, Beijing 2008

Better known as the Bird’s Nest due to its distinctive steel lattice envelope, the National Stadium was designed by Swiss studio Herzog & de Meuron, with Chinese artist Ai Weiwei acting as a design consultant.

The showpiece for China’s first Olympics, the project proved controversial due to the demolitions needed to build the monumental stadium.

London Aquatics Centre by Zaha Hadid Architects, London 2012

Designed by Zaha Hadid Architects, the Aquatics Centre was an architectural highlight of the London 2012 Olympics.

Like many of the games’ venues the aquatic centre was designed to be reconfigured with a reduced capacity into a legacy mode after the competition finished.

The swooping main building was flanked with a pair of temporary wing-like seating stands, which were removed following the games.

Velodrome by Hopkins Architects, London 2012

Along with the aquatics centre, this velodrome was one of five permanent venues built on the Olympic Park for the London 2012 Olympics.

The venue is topped with a Pringle-shaped, or hyperbolic paraboloid-shaped, steel-framed roof.

It was one of three Olympic buildings – the others being Populous’ Olympic Stadium and the London Aquatics Centre – shortlisted for the Stirling Prize, although none won.

Japan National Stadium by Kengo Kuma, Tokyo 2020

Designed by Japanese architect Kengo Kuma as the centrepiece of the 2020 games, which took place in 2021 due to Covid-19, the Japan National Stadium hosted the opening and closing ceremonies as well as the athletics events.

The oval stadium was partly construct from timber, with seating covered in a latticed larch-and steel-canopy. It was wrapped in terraces that contain plants and trees.

Olympic Impact

This article is part of Dezeen’s Olympic Impact series examining the sustainability measures taken by the Paris 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games and exploring whether major sporting events compatible with the climate challenge are possible.