On the evening of November 2, 1979, the comfortable, eight-room bungalow at the corner of Cypress and Yanceyville Streets in Greensboro, North Carolina, hummed with activity. In the kitchen and dining room and in an upstairs office, men and women huddled together, making placards, practicing speeches, and fine-tuning logistics for the march and conference set to take place the following day.

Article continues after advertisement

Several women sat on the living room’s colossal empire couch talking and laughing as they stitched bolts of khaki cloth into Revolutionary Youth League uniforms for the children who were busy chasing one another through the house and across the property’s oak-canopied yard. As they laughed and played, their shouts, like hurled incantations, carried past the silhouetted limbs, toward the low clouds that blanketed the city.

The house belonged to a handsome, intellectual couple who’d found each other through radical politics and recently married. Signe Waller held a doctorate in philosophy from Columbia University but quit teaching to commit herself to grassroots political activism. Jim Waller, a physician by training, had been drawn to North Carolina by the offer of a coveted postdoc at Duke University. He’d left the medical profession to become a laborer and a labor organizer.

His new colleagues, fellow lintheads at the Haw River Granite Mill, one of the largest corduroy producers in the world, nicknamed the bespectacled, thick-whiskered ex-doctor Blackbeard. They’d come to appreciate his quirky, wry humor and to trust the workplace agitation he encouraged in the interest of their health and quality of life. He was their pirate. After eighteen months, plant management fired Jim for, the managers said, omitting the fact of his medical degree on the application—a pretense, the activists believed, convinced that spooked managers dismissed him for his relentless union organizing.

These men and women intended to be agents of history, wading into relentless currents to rudder the United States toward a far and brighter shore.

Jim wasn’t the only licensed doctor in the close-knit group. Paul Bermanzohn, Mike Nathan, and Mike’s wife, Marty, offered all who asked a short parable about why, after dedicating years to their medical training, they’d shifted their focus beyond the examining room. A doctor sits in his office and people keep hobbling in with broken legs, they’d say. The doctor sets the legs and sends the people back into the world. But they keep returning, their legs fractured once more. Curious about the cause of this epidemic, the doctor looks outside. He sees a big hole and watches as people fall in. The doctor decides to leave the office, pick up a shovel, and fill the hole.

One would have been hard-pressed to encounter a more unusual mix of people in Greensboro or most anywhere in the United States. They were Black and white and brown, men and women, young and middle-aged. Some held degrees from the country’s most prestigious universities. Others had never completed high school. And yet they all agreed that “filling the hole” meant inverting the social order, turning power over to the country’s working people. If capitalism didn’t soon collapse like the rickety house of cards they believed it to be, they’d agitate to dismantle it, textile mill by bank by distant investor.

The future society they imagined would prevent byssinosis, the debilitating brown lung disease that cut short the lives of the Piedmont’s textile workers; pay living wages; support working mothers; and deliver healthy food to all its citizens regardless of race, culture, or circumstance. These goals might not have sounded terribly radical but seeing how far short society fell of these objectives had broken their faith in the political and business establishment’s commitment to the country’s poor and working people, to the idea of America’s inevitable progress.

The people bustling around Signe and Jim’s home were not Kumbaya-singing hippies or dropouts. They rarely drank and didn’t take drugs. The ideals of the Declaration of Independence—“all men are created equal”—had led them to the melody of a siren song: “From each according to his ability, to each according to his need.” It was a hazardous amalgam sprung from American soil. While they weren’t controlled or in communication with any foreign power, they did find inspiration in the peasant revolution in China and its charismatic and ruthless philosopher-soldier, Chairman Mao Tse-tung. Mao, possessing a gift for pithy quotes, had said, “If you want to know the taste of a pear, you must change the pear by eating it yourself… If you want to know the theory and methods of revolution, you must take part in revolution. All genuine knowledge originates in direct experience.”

When the moment grew ripe for revolt, the men and women in the house on Cypress Street were prepared to taste the pear: what else, they asked, but a well-organized insurrection could overthrow a government that extracted its immense wealth and power from Native American land, the toil of Black slaves, and the exploitation of the working poor? These men and women intended to be agents of history, wading into relentless currents to rudder the United States toward a far and brighter shore.

*

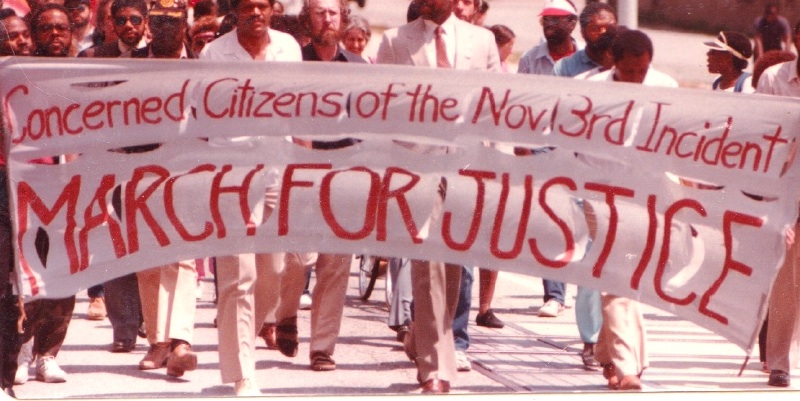

The next day’s Anti-Klan March and Conference would call attention to a new wave of white supremacist and Ku Klux Klan activity percolating around the South. More meaningfully, perhaps, the event aimed to “educate the people” about the peculiar way the country’s economics still depended on racial disparities, and how the Klan’s racist ideas kept Black and white workers from coming together to make unified demands of the Piedmont’s powerful mill owners. With good weather, the event might be the largest labor march in Greensboro since the radical uprisings of Great Depression, causing the owners of the city’s hulking textile mills, which whirred and clacked around the clock churning out cotton fabric, to tremble.

These few dozen activists in North Carolina’s textile capital were not alone. They constituted one local cadre of an organization with its headquarters in New York’s Chinatown and core groups in Boston, Baltimore, Detroit, Chicago, Denver, San Diego, and Los Angeles. Total membership reached possibly as high as three thousand, though the activists avoided keeping a list of names that could fall into the hands of the FBI or any law enforcement agency antagonistic to the group’s revolutionary goals.

Less than a month earlier, the organization had gone by the relatively innocuous name Workers Viewpoint Organization (WVO). At its conference in October, a majority of members agreed that it no longer made sense to obscure their underlying politics. In the depths of America’s Cold War with the Soviet Union, they changed their name to the Communist Workers Party (CWP). Addressing the membership, the general secretary of the group, a charismatic Chinese American named Jerry Tung, steeled party members to fight for a new society, which could “only be forged by blood—by sacrificing the most sacred of all things—our lives.”

The Anti-Klan March and Conference would be the organization’s first significant action under the new moniker Communist Workers Party.

*

In the midst of the Cypress Street excitement, Thomas Anderson, known to all as Big Man, raised a concern. If these brazen organizers were going to provoke the Klan, they would need “expert gunmen, somebody who knows how to shoot” to protect them.

Big Man arrived in Greensboro in 1950 and had been employed in the mills for nearly thirty years. Despite Greensboro’s carefully cultivated reputation as a progressive southern city, Big Man’s experience led him to a different view. “Greensboro,” he believed, “is about the craziest city in the South. It’s worser than Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana.” Older than the others in the house, his physical presence as well as his long tenure as a mill worker in Greensboro commanded respect. “It’s a lot of things that happens in the South,” he said. Growing up Black in Greenwood, South Carolina in the 1920s and ’30s, he’d learned what the Klan was capable of. “If you attack the Klan, you would most certainly, sooner or later, get hurt… I know they has kilt people, drag people down the road and hang ’em up in trees, and shoot them ’til there is nothing left but the rope. And gotten away with it.”10 As the 1970s gave to the 1980s, fear of the Klan still slipped through American time, irreducible and intact, like the slither of a dream-snake through the cerebellum, even for rugged, middle-aged Big Man.

*

Something else bothered Big Man. He believed some in the group were growing too comfortable with the possibility of violence. They’d picked up a slogan circulating through South—“Death to the Klan”—and printed it on their flyers and posters. They’d printed an open letter to the Klan calling them “scum,” threatening to “chase [them] off the face of the earth.” Referring to the Workers Viewpoint Organization’s participation in a rally four months earlier that succeeded in interrupting a Klan screening of the racist 1915 film Birth of a Nation, Jim Waller had confided, “Big Man, the next time we meet the Ku Klux Klan, we’re going to have to be ready to kill.”

Big Man knew that for all their revolutionary bluster, these radicals, men and women he cared deeply for, weren’t prepared to trade shots with the Klan. Two policemen had been at the demonstration against the Birth of a Nation screening. That shirt-thin blue line likely prevented the armed Klansmen from opening fire and massacring the hundred raucous demonstrators chanting anti-Klan slogans. Big Man thought the CWP should stay focused on building more powerful unions in the mills, not risk confrontations with the Klan. Their “Death to the Klan” agitation defied his common sense.

Change, he’d learned from experience, didn’t just happen; it required pressure and risk.

People heard Big Man out. Maybe, some suggested, they should request that residents along the march route stand on their porches with guns.

*

It was growing late when Nelson Johnson, the thirty-six-year-old leader of the local cadre, strode into the house, his five-foot-eight-inch frame tipped slightly forward, a slight hitch in his confident gait. His bright eyes, which could shift in an instant from empathy to defiance, flashed with optimism. This multiracial CWP group in the Carolina Piedmont wouldn’t have existed without the Promethean gift of Nelson’s hopeful fire, his vision of a more equal future, his resilient network of personal and professional relationships in Greensboro’s Black community, and his talent for knitting together coalitions across class and age, among Black professionals, students, and the poor—and, more recently, across race. The respect he commanded derived not only from charisma and astute social analysis, but from the courage he’d demonstrated in confronting powerful people and institutions and winning labor strikes, rent strikes, and political campaigns. Change, he’d learned from experience, didn’t just happen; it required pressure and risk.

Many CWP members, not only in Greensboro, but around the country, had followed Nelson into the organization, believing in his leadership and his quest for equality more than any ideology. He’d never been drawn to the secret guerrilla tactics of roaming, underground radicals—Black and white—like the Black Liberation Army or the Weather Underground, who burst into moments of space and time to explode the “establishment’s” symbols of power. Instead, he’d chosen the door-to-door, meeting-to-meeting grind of building unity around a vision of how America’s vast power and prosperity might be shared with the poor and the marginalized.

Pacing back and forth in the living room, Nelson countered Big Man in a “lawyerly fashion.” Like big man he’d come to Greensboro from the agricultural, Black Belt South, but a generation younger, he located existential threats in the biases and inertia of institutions not the angry face of a racist vigilante. The Klan, Nelson believed, wouldn’t dare ride into a Black neighborhood in broad daylight. The Klan were night riders, not day raiders, right? Big Man couldn’t deny this.

The real threat to the march then, Nelson continued, wasn’t the Klan, but the Greensboro Police Department (GPD). He ticked off the list of the department’s most recent offenses: When he applied for a parade permit, he’d had no choice but to accept the police demand that the CWP not carry guns during the march, though he believed the stipulation might infringe on the group’s constitutional rights. Despite agreeing to these rules, it took two weeks, instead of the standard seventy-two hours, for the permit to be issued. And these weren’t the only signs that the police were intent on disrupting the event he and his comrades had been planning for two months.

As Nelson’s wife, Joyce, and others stuck flyers to electric poles around the city, they noticed that the police tailing them and tearing the posters down. The church that offered its sanctuary for the post-march conference withdrew the invitation when a rumor of potential violence reached them. Joyce traced the rumor back to the police department, yet no one at the GPD had warned Nelson or any other CWP members of threats to their safety.

No, the enemy they would face the next day, Nelson believed, wasn’t the vigilante Klan. The police would be everywhere during the march, he said, looking for a violation of the permit, protecting the interests of the businessmen who ran the city.

If the police couldn’t find a violation, they might be willing to stage one, Nelson warned. As the women sat sewing on the living room couch, Nelson demonstrated how a provocateur’s jacket might swing open, revealing a weapon, granting the cops an opening to shut down the march, or worse, provoke a riot: “If anyone should come into the march with a weapon, that person is either just an innocent person with a gun or a provocateur, and more likely it’s a provocateur…immediately pull away from the person and leave him alone, and let the police take him….We [will] not be baited into responding to violence with violence.”

Remember, said Nelson, the police get away with murder.

__________________________________

From Morningside: The 1979 Greensboro Massacre and the Struggle for an American City’s Soul by Aran Shetterly. Copyright © 2024. Available from Amistad Press, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Featured image: The Romero Institute, used under CC BY SA 3.0.