My new novel imagines a world where a right-wing US government passes an executive order that calls for the mass incarceration of people based on their ethnicity. Protest movements confront the Constitutional crisis until they fizzle out; Democrats barely put up a fight. It may not be exactly what’s happening under the Trump administration, but readers have seen the parallels very clearly. Articles have described the book as “eerily prescient,” “terrifyingly close,” and “distressing in its realism.” The New York Times called it “timely.” So did the Washington Post. So did Tony Tulathimutte.

Article continues after advertisement

Each of these instances is meant to be complimentary about the book, and while I don’t disagree that the concept matches a lot of current headlines, it was never my intent to publish a timely novel. When I started writing Mỹ Documents seven years ago, I hoped it would feel urgent, but no part of me wanted to see the book reflected in the world around me. At a recent book event, an aspiring writer asked me if being in this horrific political climate had gotten me excited for the sales potential. “Be honest,” he asked. “Are you stoked?”

I told him I wasn’t. (I am also not sure I have ever been “stoked.”) And I worried that in all of the conversation around Mỹ Documents being timely, that its actual conflicts and themes had been obfuscated by the emphasis on the news cycle. Fiction that attempts to be timely risks coming across as “social justice fanfic.” These books—often dubbed “novels of ideas”—use their characters as mouthpieces for political motives and establish plots with clear good guys and villains. More than that, political art that seeks only to speak to this moment tends to flatten narrative in its attempt to be relevant.

More than that, political art that seeks only to speak to this moment tends to flatten narrative in its attempt to be relevant.

With Mỹ Documents, I pulled from this country’s history of incarcerating Japanese American citizens during WWII, the legacy of the Vietnam War, and the contemporary horrors of migrant detention. But it is deliberately not political art. Mỹ Documents is not a book with a clear moral message. Instead, I wrote it to wrestle with the ambiguities of surviving and reckoning with political realities. Through its characters, I wanted to challenge the idea that resilience is a brave or admirable trait.

Also, for a book about people who suddenly find their freedoms and rights stripped from them, I think Mỹ Documents is pretty funny. Even in camp, the characters are petty and often selfish. It’s a family drama set in a bleak environment. The tension of the book exists in that gap: the existential dread of camp and also the mundanity of the characters’ day to day life.

One piece of advice you get when you publish a book is to never look at the Goodreads reviews. I have always disregarded this personally, since the site offers a wealth of fascinating takes. Even the ones that can be discarded are at least amusing. I recall a review of my first novel where the Goodreads user lamented being tricked into reading literary fiction. (It’s unclear who “tricked” her exactly.) She still gave New Waves three stars.

As an author, Goodreads offers you the ability to respond to your reviewers—a thing no one should ever, ever do. (I noticed recently that if you have an author account and you click through to a one-star review, the site gives you a warning about not replying.) Still, I was still tempted to respond to one user who found the concept of Mỹ Documents totally implausible. She admitted that, yes, Japanese Americans had been incarcerated less than a hundred years ago, but she couldn’t imagine anything like that happening again. Certainly not here in America.

A part of me wanted to tell her that ICE detains over 250,000 migrants a year—that over the past decade, it had been millions; that just this month, Trump promised to multiply ICE’s budget by thirteenfold, to $45 billion, specifically for incarceration; that he’d already invoked the Alien Enemies Act, the threadbare wartime authority FDR used to justify rounding up Japanese Americans, to deport people to El Salvador.

I didn’t reply, of course. But in a way, I admired this user even if she hadn’t liked my book. She had read it, completely disconnected to the reality of this political moment. For her, it lived out of time and she’d judged it on the merits of what was between the pages. I wrote a book not so it would be read today, but to be enjoyed and interrogated decades from now. This is the goal of most novelists, the earnest hope that a story might not get stuck in the moment it was published but to endure for years to come. If Mỹ Documents is timely today, I want it to be meaningful tomorrow. That’s what would make me stoked.

_______________________

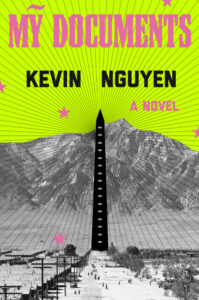

Kevin Nguyen’s Mỹ Documents is available now from One World.