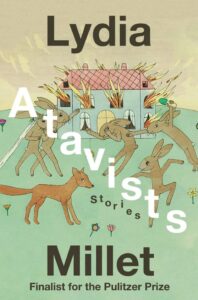

Read Lydia Millet’s fiction from her first novel, Omnivores (1996) to her new short story collection, Atavists, and you’ll trace an evolutionary arc of American culture from the Home Shopping Network to AI and LARP. There are consistencies through the years—climate change, bodybuilding, birds, dinosaurs, disjointed relationships, for instance—but her work never feels repetitive. Instead it feels inventive, as she keeps pushing further into her universe.

In stories, like “Artist,” Millet drills deep into the generational paradox. “Shelley was smart as a tack. But she was all about the spin…Somewhere, raising her girls, Helen had taken a wrong turn. Left out the part about morality.” When Helen suggests she take a progressive agenda with her talent agency clients, Shelley pushes back. “Mom. Noam Chomsky’s a dinosaur. And not even a ferocious T.rex, either. More of a brontosaurus. A lumbering plant-eater.”

Millet touches upon tech bros in her tale of the futurist, an academic who considers ethics “stodgy” and AI a “spiritual revelation.” His experience of glimpsing “a dense swoop of black dots that were birds” on a run in a port city in Europe becomes most meaningful to him when it is reiterated in a YouTube video: “Swallows. They formed and re-formed in graceful morphing shapes in the blink of a human eye. The video was captioned Celestial choreography. He’d understood it right away. The birds were barely alive. More like fragments of information in the sky. And then he’d had the feeling. Power. Euphoria. The smooth, hard glint of steel. Flesh into digits, wings into pixels. Blood and oxygen into will, will into majesty.”

Each new book is a revelation, as Millet spins her narratives through an original, satiric, often genre-bending lens. Her voice keeps getting sharper—simultaneously funnier and more painful. Our email conversation reached from my office in wildfire-prone Sonoma County to her home in the Sonoran desert near Tucson, where she works at the Center for Biological Diversity.

*

Jane Ciabattari: When did you start working on this new collection of stories, your third (after 2018 Fight No More, which won the American Academy of Arts and Sciences short fiction award and Love in Infant Monkeys, a 2010 Pulitzer Prize finalist that features weird animal stories about Madonna, Sharon Stone, and other celebrities)?

There are so many ways we use the suffix -ist, and I wanted to play with that.

Lydia Millet: About three years ago.

JC: How did you come up with the title? And what is its meaning to you? Did you write the linked stories around the concept of the title?

LM: Actually the original title wasn’t a word but a word fragment—“The -ists”—and that proved difficult for the hardworking people who have to talk about the book in order to help sell it. So I chose an alternate that is a word. Albeit a slightly obscure one. Atavists was the only -ist I could think of that connected to all the -ist characters in the collection. I like the word for its charged quality, its inherent conflicts and judgments, its dual application in biology and psychology/criminology. “Atavistic” refers both to a return to a primordial form, like when a vestigial gill shows up on a newborn, and historically to a supposed brutishness and violence of character. What a strange, dark abyss of a word.

JC: The stories are set post-pandemic, some as recently as 2025, it seems. What are the complications of writing stories so close to the now?

LM: Many! Everything changes so fast, everything new becomes old at a breakneck pace. These tales were written before the recent election, and so, in a sense, are already quaint.

JC: Why set the stories in Los Angeles? What does that represent to you?

LM: I’ve set a lot of my books in LA—I lived there for a few years at a formative moment in my 20s and most of my family lives there now. It’s still a place I spend time, full of friends and loved ones, which remains both familiar and strange. It used to seem to me, as Leonard Cohen sang about America, like the cradle of the best and of the worst. Or one of the cradles. Now I’m not sure exactly where the best is, in America. Maybe the forests and deserts and meadows. Maybe in the last of the wild places.

JC: Your characters cover a wide range of generations, professions, interests; you write of a therapist, a futurist, a dramatist, a fetishist, an artist, a terrorist, a mixologist a futurist, an insurrectionist, a cultist, and more. How did you select these categories, these areas of interest?

LM: Hmm. I wove toward them like a drunkard? There are so many ways we use the suffix -ist, and I wanted to play with that…it essentially means someone who advocates for something or believes in it, but can also just indicate the form of someone’s labor or their psychological tendency (say, narcissist). There’s a fluidity in -ist that’s interesting.

JC: How did you research these characters, who exist is such specific universes?

LM: Not much research here, at least not conscious. Impressions and exaggerations of people I’ve met, people I’ve not met, people whose shadows and stereotypes flicker along in the rush and ugly-beautiful damages and triumphs of culture.

I just follow the threads of the sentences and the made-up personalities and see where the doors and windows appear.

JC: You interweave the characters in fascinating ways. For instance, a character in one story is the niece of a character in another story. She runs into her uncle in a bar with a group of men including a muscle man who ghosted her with a painful text: “Sorry, but you’re just too fat for me.” This thread, and her search for revenge, runs through yet another story, with a startling conclusion. How did this echoes of stories evolve?

LM: (Not an interesting answer!) Writing, I just follow the threads of the sentences and the made-up personalities and see where the doors and windows appear. It’s like a walk through a house, a walk through a city, or a walk through a maze at the edge of the woods.

JC: How did you go about choosing the order of the stories?

LM: They got rearranged a bit, mostly for flow and so that the touchstones worked together.

JC: When last we had a conversation it was about your novel Dinosaurs. How do you balance writing novels and story collections?

LM: I write stories to relax, usually while I’m between novels or between novel drafts.

JC: Which other writers (or artists, musicians, filmmakers, others) are you paying attention to now?

LM: I’m preoccupied by the crises in our politics, right now, and when I’m not reading about those, and in a state of repulsion and anger, I’ve been tending to read nonfiction. I loved wildlife journalist Brandon Keim’s new book Meet the Neighbors, for example. Oh and I *am* reading one exciting novel right now: The Harmattan Winds, by Sylvain Trudel. A translation from the French (Canadian). Highly recommend.

JC: What are you working on now/next? (How many projects?!)

LM: Three novels in various stages of disarray.

__________________________________

Atavists: Stories by Lydia Millet is available from W.W. Norton & Company.