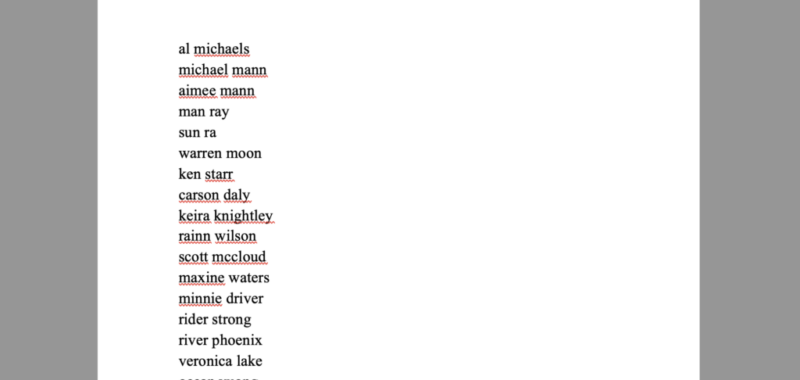

An early draft of “Sissy Spacek.”

For our series Making of a Poem, we’re asking poets to dissect the poems they’ve published in our pages. Mark Leidner’s poem “Sissy Spacek” appears in the new Fall issue of the Review, no. 249.

How did this poem start for you? Was it with an image, an idea, a phrase, or something else?

When the novel Heat 2 by Michael Mann and Meg Gardiner came out, I thought about how weird it would be to be a man whose name was “Mann.” I thought about how arbitrary names are, and how strange it would be to be assigned such an empty template. I tried to write a poem made up of people with Man or Mann in their names, but the only three I could think of (Michael Mann, Aimee Mann, and Man Ray) weren’t enough for a poem. I added “Al Michaels,” which is an odd name for different reasons: he seems to have two first names, and both are extremely ordinary.

Maybe insecurity about my own relatively ordinary first name fueled these concerns.

Regardless, I liked how “Michael Mann” and “Al Michaels” mirrored one another in banality. For a while, I tried to think of names that were like “Al Michaels” (two first names, both exceedingly common) but that also proved insufficiently interesting. Trying to salvage the time I’d put in so far, I gave up on my original idea and broadened the search to famous names that had familiar or interesting nouns in them, the total opposite of “Al Michaels.” That’s when the poem finally found a runway.

Were you thinking of any other poems or works of art while you wrote it?

Not really, though I suppose Inger Christensen’s Alphabet, which is the pinnacle of List Poem Mountain, is never far from mind when making a list poem with small units (one or two words or short phrases, as opposed to one with longer sentences or stories).

How did writing the first draft feel to you? Did it come easily, or was it difficult? Are there hard and easy poems?

The first draft came easily, but only after I realized the rule that the list was going to follow. Some poems are hard, though. Maximum difficulty would be medium-length lyrical meditations on something important, like love or death or culture or a memory. Those are almost impossible for me to write, and if I ever catch myself starting one, I have to stop immediately, because I know it will take me ten years and I’ll never get anything I like out of it. Poems that begin as jokes or absurd premises but attempt to transcend those beginnings I would categorize as medium difficulty. The easiest poems to write are list poems. They are harder to end than to begin, but the worst a list poem can become is pleasantly frustrating, like dying in a video game you enjoy playing.

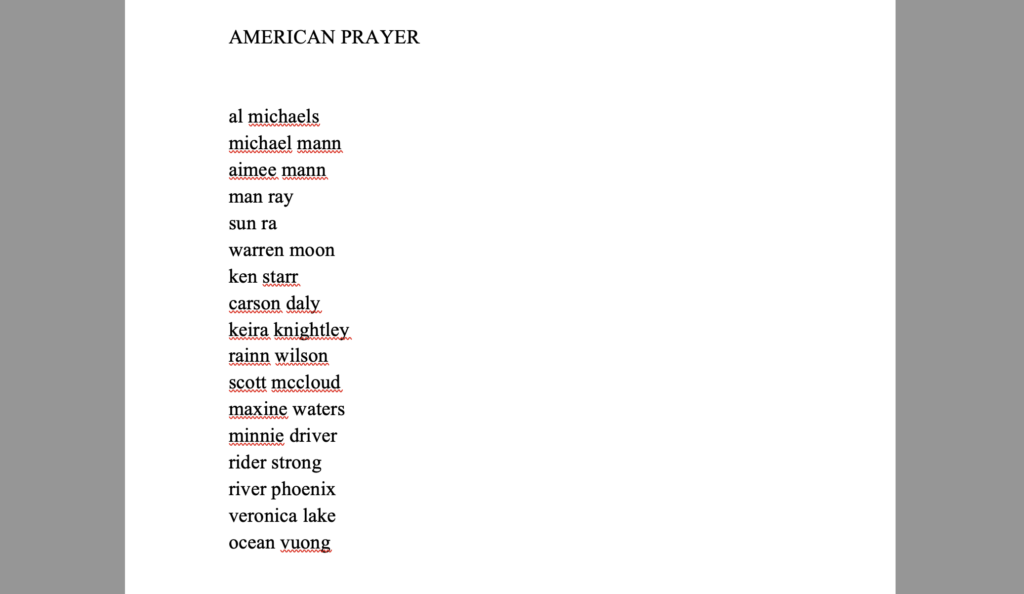

A later draft.

How about the second draft? The third? How many drafts were there and what were the primary differences between them?

After settling on celebrity names with evocative nouns, I narrowed the constraint to names that referenced space, earthly elements, and human or animal subjectivity (like aging or suffering). Under this regime, three man names was too many. I kept “Man Ray” because “Ray” evoked space, especially after “Sun Ra,” but cut “Aimee Mann” and “Michael Mann.” I also cut “Minnie Driver” and “Rider Strong,” even though they were probably my favorite pairing, because they weren’t quite on theme. Riding and driving evoked technology, cars, stuff like that. By removing them, the progression from space to earthly elements to biological subjectivity became a bigger part of the poem.

How did you come up with the title for this poem? Were there other titles you thought about for this poem? What were a few runner-ups? Why didn’t you go with them?

At first it was called “American Prayer,” which I didn’t like. Both “American” and “Prayer” suggest an interpretation of the poem that would be unfortunate if forced upon readers. So I changed it to “Namesong,” which I also didn’t like. Calling the poem a “song” felt like my heavy-handed attempt to elevate it into something it’s not. Or, if it is a song, I don’t want to be the one insisting on that. Then it was just “Names” for a while—but where the previous two titles gave too much predetermining context, “Names” gives too little. It would be like titling a poem made of words “Words.” So I was stuck with a poem I liked and no good title. A better problem to have than the alternative.

The breakthrough came randomly. I was listening to a podcast comparing the 2013 version of Carrie to the classic 1976 version starring Sissy Spacek. I realized that her name fit the cosmic theme I was going for in the beginning, so I made it the first line. Soon it got promoted to title. Instead of a “container” title that categorized all the list items together while remaining separate from them, it was a metonymic title, both an item in the list and representative of the poem as a whole. Metonymy has saved my ass, I thought.

When did you know this poem was finished? Were you right about that? Is it finished after all?

After the basic structure and ending was set in place, every now and again I would hear a celebrity name I hadn’t thought of and try to weave it in, only to create new problems and, usually, take it back out. When it was accepted for publication, that was the real ending of the poem. If an editor likes something and wants to publish it, then I let go of trying to improve it. There is probably no end to the number of good names out there waiting to be remembered.

Mark Leidner is the author of three books of poetry.