Photographs courtesy of Nora Claire Miller.

Whenever I open the fridge, the same poem falls off the door: “you against the green screen, a place / without history,” from Tracy Fuad’s collection about:blank.

The poem is printed on a postcard, and it has been falling off my fridge for over a year now. I sometimes think about moving it or using a better magnet. But I like that the postcard can be dislodged easily. Wherever the poem falls, the surface it lands on—linoleum floor, grocery bag, shoe—becomes its own green screen, its own substance disconnected from time.

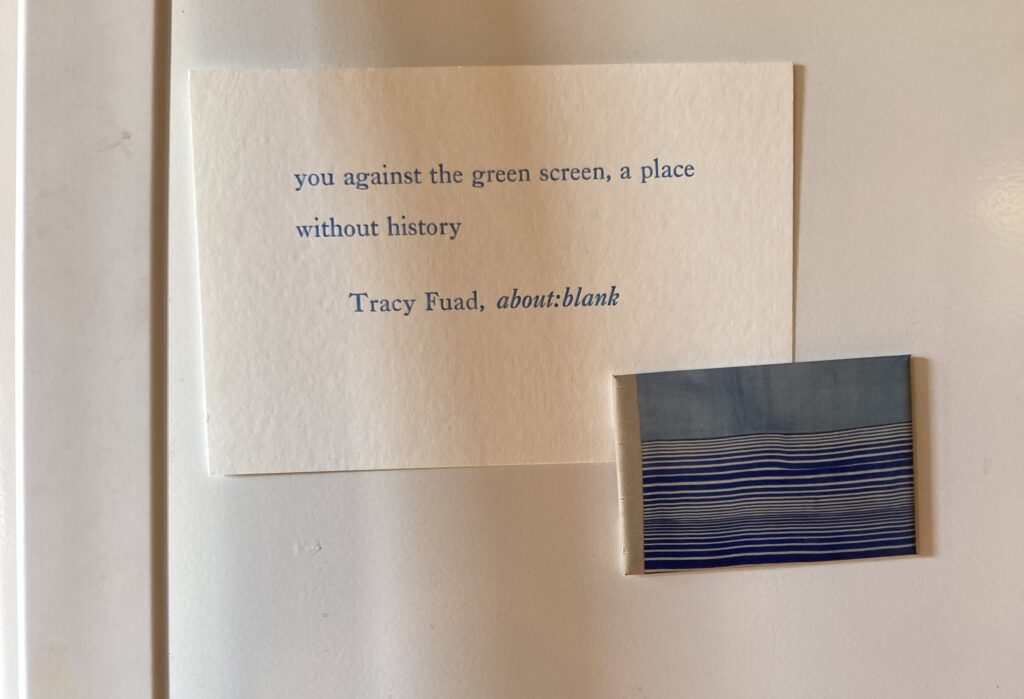

Each month, I get two copies of a new letterpress-printed poem in an envelope—one to keep and one to send, according to Kate Gibbel, the editor of the Vermont-based Send Me Press. Founded in 2021, SMP only sells two things on their website: postcards, and a bumper sticker that says I LOVE POEMS. I’ve sent a few of the duplicate postcards to friends, but I usually forget, so there are two copies of lots of poems around my house. I like to place the postcards situationally. I put a poem by Liam O’Brien on the kitchen table. “cold salt hot little hand,” I say to myself every time I grab the salt. I have a poem by Micky Bayonne propped beside a lava lamp: “I buried into the fissure, the glow! / How could I not be drawn in? Spun down?” There’s also a copy in my car. The fissure, the glow! I think often as I drive, my car yelling I LOVE POEMS at the world.

Recently I drove to visit Kate while she was printing. I watched her pick up each metal letter and arrange them on a tray. It takes many hours of work to typeset a poem like this, print the copies on the giant press, and then to cut the postcards, address and stamp each envelope, and mail them out.

I sometimes ask Kate if she’d ever consider switching to a less tedious way of making postcards. But Kate always says no. Like the poem that keeps falling off my fridge, the time it takes is the whole point.

—Nora Claire Miller

Enjambment makes music but it can be an instrument of metaphysics too. Read “it was broke / Before they made the avenue” and you’re situated in a certain period, “Zigzag so you couldn’t cruise” and you’re in another moment altogether. Still, the era of no-avenue endures on that previous line.

I’m quoting from a new book of poetry by Gabriel Palacios, A Ten Peso Burial for Which Truth I Sign, which floats and cuts with vertiginous acuity through stuff piled around the Southwest. In Palacios’s poems, sublime lyric density is a means of perception, a form of infrared. It reveals specificities I want to call enjambed images. I don’t mean descriptions spanning several lines of verse. I mean images that fuse different surfaces and compact time: “My child’s eyeball strobic in the wide-brimmed hatted / death’s head given placard.”

Time never progresses, it accrues in place (“Like anaphylaxis, additional mornings / did ensue”), and Palacios’s verse extrudes the spectral accumulations. I’m moved by how he writes about ancestors, past selves, scarred public space. Two sequences orbit seraphs and holographs, incandescent unphotographs, and imperial nostalgias like the neon ruins of the Spanish Trail Motel. Interacting scales of menace emerge elliptically: “this creditor / in sequined ball cap,” “Colonial geometry,” “Dumb police,” “Sinaloa / deathshanty of desiccated shrimp boats,” “A pivotal murder on your mother’s side / Changed by the telling.” Thinking in this book is no abstract process; every poem is full of things. Part of the work’s power lies in Palacios’s subtle sense of metonymy, the shrewd and often funny way he glosses details, making us see something sharp and discrete while feeling something vast and ambient. “Airport parking annexes rewild / To an amplitude of green Big Paint would call / Antiquity.” “Aesthetically speaking / You smell smoke here.”

—Margaret Ross

Emily Jungmin Yoon’s first collection of poems explores the intersections of public and personal histories—forging a harrowing art out of the words of Korean “comfort women” and their narratives of sexual violence during and in the aftermath of World War II. In her second collection, Find Me as the Creature I Am, Yoon’s gaze is turned to intimacy. To highlight her interest in our shared “creatureliness,” she includes a host of nonhuman animals in the poems, often as figures for our animal needs and desires. In the opening poem, “What Carries Us,” she writes: “Imagine love as a horse. // Think about us—a distance / apart only a flying thing could connect us— // standing and pacing, tamed and watching, // then finally with each other, laughing, / as if to collapse, unbridled as wild horses.” Distance and connection, the human and the animal, stillness and transit, joy and collapse—these are the tensions that run throughout the collection. In another poem, occasioned in part by the statement that there is not “ ‘an eco-friendly’ way to swim with dolphins,” the speaker declares, “We do not have to touch everything we love.” Yoon is an expert at cataloguing horrors: climate change, natural disasters, a ceaseless predilection for violence, racism, and intolerance, the pain of migration. But there’s wonder and beauty here too. The book’s most arresting moments are quiet scenes between people, scenes of parting and of goodbyes, in elegies for grandparents, and in proper love poems. It includes some of the most beautiful wedding vows I’ve ever read, a charming poem about friendship among poets, and another about looking to the constellations, about feeling lonely and small, but being in the world together. Her poems are a space where these realities can co-linger, can be weighed and contemplated. Cynicism never blots out the marvels; the marvels, in turn, never obscure the world of threat we all belong to. They are, in Yoon’s book, part of moving—down the page of the poem, or forward into the future—closer to the creatures we are. “In all the futures I am capable of prayer for,” she writes, “you are not alone—you are alive.”

—Richie Hofmann