Betty Joel was one of the UK’s most successful designers and furniture makers during the 1920s and 30s. As part of our Art Deco Centenary series, her great-nephew, Clive Stewart-Lockhart, picks his favourite of Joel’s designs.

Joel’s design career lasted less than two decades but was marked by huge achievements.

As chief designer and figurehead of the eponymous brand she co-founded with her husband, she created pieces for some of interwar Britain’s most iconic interiors and worked on private commissions for the likes of politician Winston Churchill.

Her work attracted critical acclaim, winning prizes at the Royal Academy and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, as well as commercial success, with the Betty Joel brand employing more than 80 craftspeople at a purpose-built factory in Kingston upon Thames.

She was a prominent contemporary voice at the forefront of art deco, though her legacy has largely been forgotten after she suddenly and permanently turned her back on design shortly before world war two.

The untold story of Joel’s working life is detailed in an upcoming book titled Betty Joel: Furniture Maker, Designer and Businesswoman in 1920s And 30s Britain.

Here, the book’s author Stewart-Lockhart, a former Antiques Roadshow expert who knew her well in her later years, selects his favourite Joel designs:

Drawing room in The 1932 Flat, London

“With no formal design or marketing training, it is remarkable what Betty achieved in the 17 years that she was involved with the business. She developed a close relationship with the press, in particular The Studio magazine, and this colour photo appeared in an article by Derek Patmore in 1932. It shows the drawing room in what she called The 1932 Flat.

“This flat was above a scheme done by Betty Joel for Coutts Bank in Park Lane. Four rooms were furnished with the brand’s latest designs. It was visited by 7,000 people and described in The Studio as ‘a typical example of her own highly-individual style’.

“The walls of the room are panelled in Canadian pine, with a grain resembling watered silk, and left unwaxed. The ceiling is enamelled a very pale yellowish cream, and the curtains are made in a modern tapestry in pale azure and silver.

“In contrast to the warm tones of the pine, most of the furniture in the room is made in sycamore, which is left in its natural ivory colour. The floor is parquet, and on this are laid two striking rugs. Pale tones are sharpened by a small bookshelf and occasional table painted with bright scarlet cellulose.”

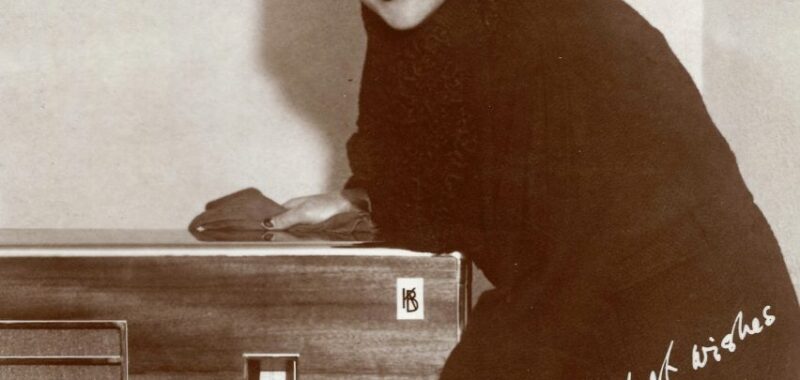

Kolster Brandes KB666 radio, 1933

“In Industrial Design and the Future, by Geoffrey Holme of The Studio in 1934, Betty comments that ‘Manufacturing firms of utility objects should call in good designers or artists, and the products should be branded with the designer’s name, as is often done on the continent’.

“The previous year, Betty had designed a cabinet for Kolster Brandes Radios for their KB666 model, which was first shown at Radiolympia, selling a remarkable 2,500 units on the first day. Kolster Brandes used a photo of Betty with a radio and the strap line ‘Betty Joel designed it’.

“This confidence that using Betty in the forefront of their marketing would guarantee sales was well rewarded. Sadly, with the advent of the transistor, most valve radios were scrapped and examples of this radio, in its warm walnut and chrome case, are now hard to come by.”

The showroom at William Hollins & Co, Nottingham, 1933

“Nottingham architecture firm FA Broadhead commissioned Betty Joel to design and provide display cabinets and furniture for the showroom of William Hollins & Co, maker of wool-cotton-blend fabric Viyella, as well as panelling and furniture for the boardroom and chairman’s office.

“The facade of the building incorporates a sun and moon motif, which Betty Joel repeated throughout the scheme. She also produced carpets with the same motifs and it was all reflected in the chrome-clad columns throughout the sales floor.

“Sadly, much of the scheme has been stripped out, but two rooms still survive.”

Sir Stewart Duke Elder’s consulting room, London, 1934

“Betty Joel worked with a number of prominent architects throughout the 1930s, and in 1932 she was commissioned by Wimperis, Simpson and Guthrie, who did much work for the Grosvenor Estate, to fit out 63 Harley Street.

“Much of the scheme must have been a close collaboration as it incorporated a number of typically Betty Joel features, particularly the ‘ship’s grille’ radiator covers, which appear in almost every one of her schemes.

“The house included a beautifully panelled round consulting room with a curved desk, the panelling with fitted bookcases.

“On an upper floor is a large, fitted bookcase/desk which, despite the passage of 80 years is still in place and in use. The current owners cherish the interiors, and it is a remarkable survival of the period.”

Longcase clock in sycamore and glass with a pair of console tables, silverware unknown, circa 1937

“Betty and her husband designed quantities of furniture for cinema and theatre, often supplying it and then selling it later, thus getting paid twice for the same piece.

“I had always assumed that these sycamore clocks with glass rod supports were for film sets, but they may just have been designed for private clients.

“This example’s hour markers spell ‘Marguerite’, while another was made with ‘Basil and Leah’. Who were they? Were they characters in a film, or simply the clients who commissioned it?

“Another version – with ‘Tempus Fugit’ – was in the collection of the music mogul Seymour Stein, who signed the Ramones and Madonna, among others.”

Rug made in Tianjin, 1937

“Betty’s childhood in China seems to have had little effect on her design style. She did, however, have all her rugs made in Tianjin to her own designs. She commented that the finished rug would be back in London six weeks from the design arriving at the carpet factory in Tianjin.

“Her rugs feature in many interior shots in the 1930s, and the V&A and Museum of the Home both have fine examples.

“In 1937, Betty was asked to produce a rug for Rugs and Carpets, an International Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Exhibited alongside pieces by every major rug designer of the day, this rug won first prize.

“Following Betty’s divorce, the rug was kept by her husband until his business went bankrupt in 1951. It disappeared for nearly 70 years, resurfacing in the family of the buyer who bought it from the administrators. It has the typical Betty Joel BJ monogram in the style of a Chinese character, as do almost all her rugs.”

Lobby of the Daily Express Building, London, 1932

“Betty Joel’s cabinet makers were mostly drawn from the naval and yacht-fitting trade and, by the mid-1930s, they were producing large quantities of furniture, panelling and doors.

“The Daily Express building has a striking facade in Vitrolite and clear glass. The lobby was designed by Robert Atkinson, and Betty Joel provided steel and wood-faced desks for the receptionists that were made by Cox and Company rather than her usual cabinet makers.

“She also designed some bent-chrome chairs in the style of Marcel Breuer, as well as glass and chrome tables. The whole scheme is overlooked by two huge relief panels by Eric Aumonier. Sadly all the furniture has gone, though the interior space and panels are, fortunately, still in place.”

Sycamore stepped chest, 1930

“Made in English sycamore, this stepped small chest is a quintessentially art deco piece, although Betty would not have recognised that description.

“The 1925 Arts Decoratifs Exhibition in Paris paved the way for new shapes and designs in furniture, and the stepped chest exemplifies this perfectly.

“Made in 1930, the piece featured in the show flat that Betty furnished in 1932 above Coutts Bank in Park Lane. It incorporates a typical Betty Joel feature with a sprung ball beating catch beneath each drawer front.”

Cocktail cabinet, 1933

“In the years following the first world war, the domestic interior changed dramatically. These new interiors required new pieces of furniture, and the cocktail cabinet was, perhaps, the most obvious example.

“Betty Joel produced large numbers of its design over much of the 1920s and 30s, making few changes to the basic design. This design with contrasting panels of timber was made in 1933 and has a pull-out glass shelf between the upper stage and the drawers below.

“By the late 1930s the short legs had been replaced by a plinth base. This was thought by Betty to make the life of the housewife easier, as no dust or dropped items could gather beneath it.”

The images are courtesy of Token Press.

Art Deco Centenary

This article is part of Dezeen’s Art Deco Centenary series, which explores art deco architecture and design 100 years on from the “arts décoratifs” exposition in Paris that later gave the style its name.

The post Nine designs by Britain's forgotten queen of art deco appeared first on Dezeen.