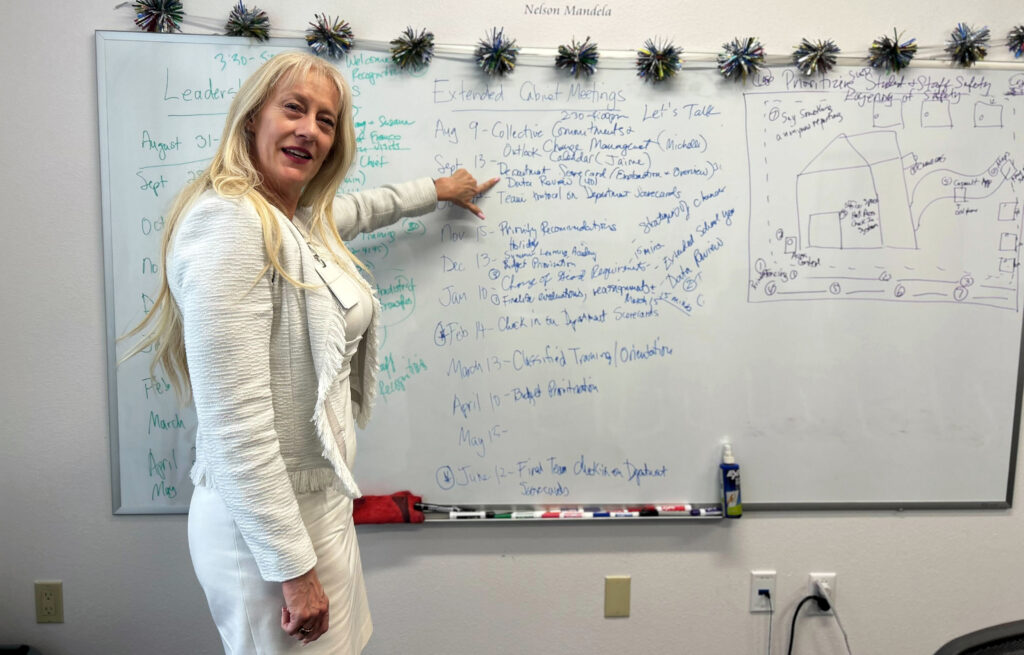

Stockton Unified Superintendent Michelle Rodriguez talks about how she arrived at her goals and plans for improving student achievement.

Credit: Lasherica Thornton/ EdSource

Stockton Unified, a mostly poverty-stricken community in San Joaquin County, has become known for its legal troubles, financial issues and superintendent turnover, which have, for years, distracted the low-performing school district from addressing student achievement. Most of the district’s nearly 40,000 students have failed to meet state standards in English and math.

Becoming superintendent in July 2023, Michelle Rodriguez knew those facts to be true. Rodriguez, the 14th superintendent to lead the district in less than two decades, said she was determined to change SUSD’s troubled reputation by focusing on students, creating stability, restoring public trust and engaging the community “one interaction, one decision, one day at a time.”

But without “actually digging in to find out what is happening,” Rodriguez refused at the start to make assumptions about what the district faced, especially its barriers to student achievement.

“Until I get in the classroom, I probably won’t be able to answer the question about lack of student achievement here,” Rodriguez told EdSource last year.

“What I knew was that because I was the 14th superintendent in 19 years, and because of just the headlines that we had seen, we knew that we needed to make sure that we solidified the system,” she said in a recent sit-down. “Instead of making the assumption that I knew specifically what was happening, I identified four key areas that effective systems have”: quality assurance, high expectations, continuous improvement and community trust.

A little over a year since her start — aligned with those areas and guided by an initial 100-day plan, over 40 school visits and dozens of listening sessions and town halls — Rodriguez is implementing a public accountability system, 44 priority recommendations, and a district culture in which data and feedback drive change.

“Something that I’m trying to do is create new traditions and new systems to hear feedback, make changes and, kind of, move the work forward,” Rodriguez said.

A system of accountability

At the start of her superintendency, Rodriguez hosted meet-and-greets and community listening sessions in English and Spanish to identify concerns that the district needed to address; based on the sessions, there were in-person and virtual town halls to create priority recommendations with “fingerprints” of community feedback.

“We want to reach the hardest-to-reach parent. We want to reach the hardest-to-reach student,” Rodriguez said a year ago about listening and collaborating with the community to develop a plan. “And within those priority recommendations, you will see your fingerprints.”

As a result, all 44 priority recommendations, including a goal to create student success plans for certain student groups, came from those engagements.

Setting those goals was merely one part of Rodriguez’ approach.

Under the banner of It Takes All of US (the word “us” emphasized within the letters SUSD), Stockton Unified created a public accountability dashboard available in both English and Spanish.

Going Deeper

Visit Stockton Unified’s Pubic Accountability Dashboard, here

Read the 2023 State of District, here, which detailed last school year’s priorities

The dashboard includes each goal, its complexity, which of the four areas it falls under, the department(s) responsible, actions, whether it’s completed or not, outcomes and the impact of those outcomes.

Simply put, the dashboard shows the district’s progress and holds the superintendent and the other officials accountable to the goals.

Rodriguez said she didn’t want the Stockton Unified community to feel as though “we did all this work, we did all these 21 listening sessions, and now nothing happened.”

44 goals is a lot. What’s been accomplished?

Within weeks of setting the goals, Rodriguez and the district completed “easy wins.”

An easy win, for example, was providing radios for special education classrooms to address student safety. Since the pandemic, dozens of teachers and staff had reported high numbers of “elopers,” mostly special education students but also young learners, running from the classroom — a recurring problem that “no one necessarily was able to solve, or chose to solve, until now,” she said.

For each radio purchased, a staff member felt better equipped to support students, Rodriguez said.

“Things like that seem insignificant, but to the system, they had a lot of impact because now those teachers feel more at ease that if they do have a student leave the classroom, there’s a way to get help to retrieve them,” she said.

Rodriguez, also in her first few weeks, formed a student advisory group of 90 students from the district’s high schools.

The formation of the Superintendent’s Student Advisory, the first of its kind in Stockton Unified, allowed her to listen to students, such as Emily Gomez Valle, a Chavez High School junior, who said the advisory was a way for her to advocate for her peers.

Then, the district tackled short-term goals, accomplishing them in three months. The district, for instance, started conducting thorough exit interviews to understand why staff were leaving the district.

The easy wins and short-term goals were intentional, so that “people knew the superintendent was getting things done,” Rodriguez said.

Long-term goals completed in the 2023-24 school year included increased access and participation in Educators Thriving, a program that provides social-emotional support and training for teachers and other school staff. Stockton Unified is set to have two program cohorts with up to 100 educators participating this school year, according to its accountability dashboard.

Based on the need to “focus on our most vulnerable students and have an action plan that is linked to them,” Stockton Unified created specific student success plans for Black students, English learners, homeless youth and students with special needs.

Other long-term goals have addressed the district’s legal and financial woes. The San Joaquin County District Attorney’s Office, with the U.S. Attorney’s Office and the FBI, launched a criminal investigation into Stockton Unified in April 2023, after a state audit by the Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team (FCMAT) found evidence that fraud, misappropriation of funds or other illegal fiscal practices may have occurred between July 2019 and April 2022.

Millions of dollars in federal one-time Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funding, which school districts received to address the impacts of the pandemic, was the subject of the investigation. Under Rodriguez’ leadership, the school district didn’t have to repay the federal government the $6.6 million in ESSER funding that was improperly awarded for a contract.

Rodriguez’ challenge was spending the ESSER funds by their timeline.

As of March 2023, just months before she started, Stockton Unified had spent only 1.84% (over $5 million) of the more than $156 million it received in ESSER III, which must be returned to the federal government if not budgeted this month and spent by January 2025. According to Rodriguez, the district has now used all the funding, completing over 40 projects.

But the allegations about the misuse of ESSER funding triggered a 2021-22 grand jury investigation into the district’s overall spending as well. Stockton Unified, Rodriguez said in 2023, relied on and spent a lot of money on consultants, which the grand jury attributed to district staff lacking the “necessary training and guidance to execute complex district business needs.”

Stockton Unified has since identified and evaluated the consultants and increased staff expertise to take over the work, leading to a reduction in consultant costs from $886,561 last school year to an estimated $275,000 this year.

And as of June, the district has finalized 32 of 44 priority recommendations, including the easy wins, short-term goals and long-term priorities.

Still there are larger systemic and structural projects and objectives that are taking more than a year to accomplish, up until this school year or longer.

What’s left to do

Three weeks after school started in the 2023-24 school year, Rodriguez said she met a homeless student who hadn’t attended school at all. She told the student about district supports, such as transportation to school and other available resources once on campus.

“And what she said to me is, ‘How do you expect me to come to school when I haven’t bathed in a week?’” the superintendent recalled.

Such encounters highlighted the need to expand family and community partnerships, increase expectations and develop equitable action plans, all of which are among the remaining priorities meant to support students and improve their experience in Stockton Unified, Rodriguez said.

More than 82% of Stockton Unified students are socioeconomically disadvantaged, according to EdData, with many facing challenges such as the student Rodriguez encountered. Even so, there must be increased expectations for students to perform at high levels with strong support.

Using her saying, “You change experiences to change beliefs to change expectations,” Rodriguez said, “I actually have to reframe your experiences so that it changes your beliefs about students, and, then, that changes your expectations for students.”

The district will also conduct an equity audit to develop a three-year action plan. The equity audit is meant to evaluate district and school policies, practices and procedures that are inequitable and create barriers “that are getting in the way of our students,” Rodriguez said. The goal requires the district to form teams of employees from each school, which will develop a multiyear action plan.

Another accountability metric

The remaining priority recommendations will also be woven into the district’s Local Control Accountability Plan (LCAP), a key accountability requirement of the state’s Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF).

In fact, Stockton Unified’s 2024-2027 LCAP goals are to increase student academic achievement; center the whole child; provide systemic and innovative programs aligned to students’ passions, interests and talents; create meaningful partnerships; provide access and opportunities to ensure success for students with disabilities; and provide positive learning conditions and experiences for Black students to thrive.

Some of the other district priorities include:

- Investing in facilities by putting $50 million of ESSER funding into schools so that students have access to amenities such as classrooms with science labs.

- Equitably offering arts programs at the district’s 55 schools and for all students, specifically those who are Black, English learners, homeless, have special needs and/or are foster youth who benefit from “differentiated instruction,” Rodriguez said.

- Launching school and district administrator classroom visits, allowing classroom staff to get feedback and administrators to gain a better knowledge of the adopted curriculum.

- Resolving the remaining findings and corrective actions reported by the California Department of Education and the San Joaquin County Office of Education as well as the findings of grand jury, FCMAT and audit reports.

Knowing if and when to change course

In some areas, such as chronic absenteeism, Stockton Unified identified a systemic goal and improved that metric in a year’s time, but still must find solutions to continue addressing the problem. In this case, the goal was to identify solutions to chronic absenteeism, in which students miss 10% or more days in a school year. Stockton Unified data shows that chronic absenteeism, though still higher than prepandemic numbers, decreased by 3.1 percentage points from the 2022-23 to the 2023-24 school year.

Stockton Unified has a nearly 40-person child welfare team responsible for improving that rate.

“How can we celebrate that?” Rodriguez asked, “but at the same time say, ‘OK, well, what we’re doing is working. Is it working fast enough? Are there any shifts that we could continue to do?’”

Chronic absenteeism, performance indicators and other data measured over time create the challenge of knowing if, when and how to pivot a district response.

For example, even though there isn’t a specific district goal about it, Stockton Unified has been adding an intervention teacher to each K-8 school based on district data. Seventeen of 41 such teachers have been hired so far.

“When we’re looking at our KPI (key performance indicator) data, what we know is that our students aren’t making the growth that we need them to make,” Rodriguez said. The district is now using iReady data, which allows teachers to deliver adaptive lessons and includes data on student progress.

Based on fall 2023 iReady data, 35% of fourth graders were one grade level behind in English, 13% were two grade levels behind and 39% were three or more grades behind, meaning that just 12.6% were on grade level. In math, 35% of fourth graders were one grade level behind, 25% were two grade levels behind and 32% were at least three years behind, meaning only 8.4% of students were on grade level.

“What is our data actually telling us? Every quarter we’re looking at the data because we want to be able to pivot and shift quicker than just yearly,” she said.

And the district was able to do that by the end of the 2023-24 school year. In the spring 2024 semester, 24.3% of fourth graders were on grade level in English – an 11.7 percentage point increase from the previous semester. In math, fourth graders on grade level grew from 8.4% to 29% — an improvement of 20.6 percentage points.

Maintaining focus

The priorities that Stockton Unified has identified are what the district has and will continue to focus on moving forward, Rodriguez said. While the equity audit will identify needed changes over the next three years, and while the district will respond to data, the district won’t shift much from the priorities it has identified.

“If you aren’t actually focused on what you need to do, then you can be too scattered and not really have the impact that you want,” she said, adding that, “Some of these changes will not change in one single year.”

Rodriguez maintains her pledge to make those changes by dedicating the last eight years of her career to Stockton Unified — a plan that became more attainable when the school board extended her contract until 2028, or year five.

“Why aren’t kids being successful?” she said. “That cannot happen until people even believe that I’m going to stay put. I won some people over at the six-month mark. I (won) some people over at the year mark. Some people will take the two-, three- year mark.”