Imagine waking up one morning and deciding to become William Shakespeare. You have fantasized about it for years and now you’re taking the fateful step. Overcome by a heady mixture of zeal, naivete, and hubris, you’re freed from feelings of shame or guilt. Although you live in the late eighteenth rather than the early seventeenth century, time won’t be an impediment for you because you’re gifted, studious, and even visionary in a deranged sort of way. Your father is a renowned collector of the original Shakespeare’s works, an authority in the field, so this transition is in your blood. Most importantly, when you present him with your handiwork he will finally come to love you.

Article continues after advertisement

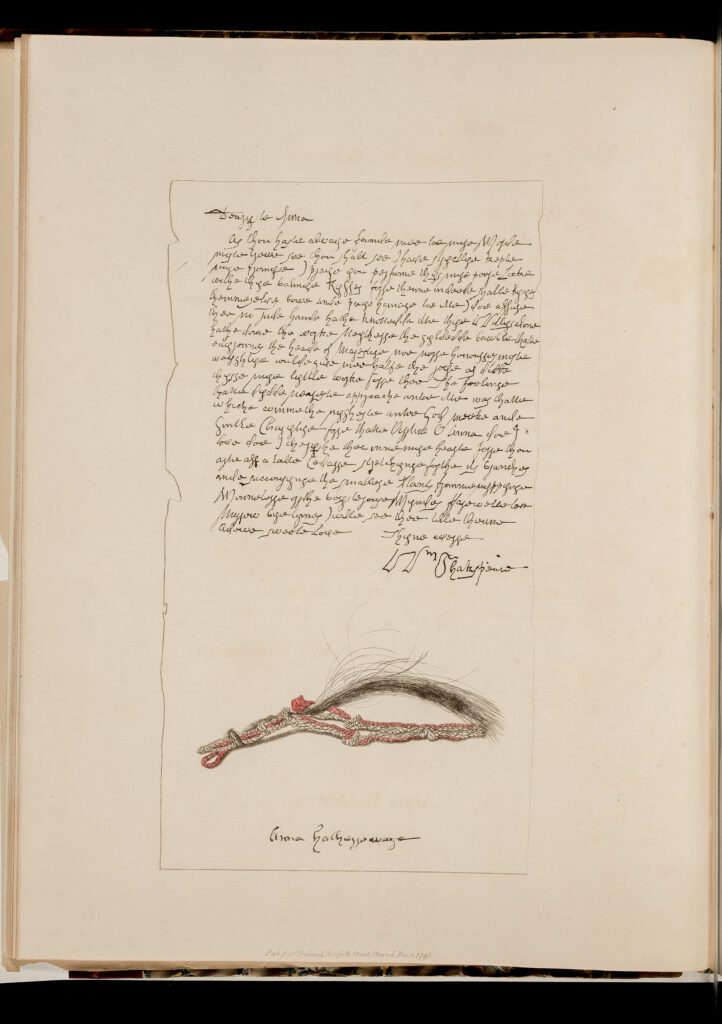

You acquire some period paper, mix the correct tone of iron gall ink, sharpen your quill. Then, in secret, you write a love letter to your wife “Anne Hatherrewaye” and attach to it a lock of his—well, your—hair bound elegantly with pink and white silk thread you find in your mother’s sewing basket. Next, you scribe some hitherto unknown poems for Anne and, emboldened, fabricate passages of the original manuscripts of Hamlet and King Lear. You produce missives to Queen Elizabeth I. Careful not to create anachronisms, you autograph and annotate the margins of books printed before the other Shakespeare’s death in 1616.

Out of fear that one of the Elizabethan playwright’s legitimate descendants might step forward to lay claim to the growing sheaf of valuable artifacts you’ve so expertly forged, you counterfeit a genealogy that proves the trove is rightfully yours. To this end, you prepare a legal document in which your alter ego—grateful for having been rescued by one of your imaginary ancestors from going to a watery grave in the River Thames—gifts him this archive in 1613. You even manufacture a coat of arms that combines your family’s with his.

William Henry Ireland’s elaborately forged love letter with hair locket from Shakespeare to Ann Hathaway. (Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society.)

Your distinguished father is so proud of you for discovering these miraculous long-lost treasures that he publishes a book to memorialize your achievement. To your anxious delight, Miscellaneous Papers and Legal Instruments under the Hand and Seal of William Shakspeare [sic] becomes a bestselling cause célèbre in 1796, the same year Matthew Gregory Lewis’s The Monk appears, a lurid Gothic novel that also relies upon deceits and masked identities. It isn’t long before your worst fears come true, and your reputation is annihilated by the eagle-eyed critic Edmund Malone, who accuses you of fraud that same fraught year. Soon enough, you are forced to confess.

Your real name is William Henry Ireland and you are destined to become one of the more notorious con men in the history of literary forgery. And you are far from alone in your criminal endeavor.

*

Literary forgery is as old as literature itself. “As soon as man set foot on the slopes of Parnassus,” wrote E.K. Chambers in his fascinating 1891 treatise The History and Motives of Literary Forgeries, “the shadow of the forger fell on the path behind him. The first historian records the first literary fraud.” Chambers here refers to Herodotus—heralded by Cicero as the “Father of History” and later excoriated as the “Father of Lies” by Plutarch since he played fast and loose with historical facts, concocting events in his Histories whenever he didn’t have first-hand knowledge and it suited his purposes.

Many accomplished forgers—most of them men—have been the children not of finaglers and fraudsters but of upstanding literary citizens in their day (or else absent fathers).

The faker of history, however, told the truth when he fingered its first forger. To wit, an Athenian scholar named Onomacritus (circa 530–480 BC), who was tasked with compiling and editing the oracles of poet-polymath Musaeus. For reasons we can only guess, based on the motivations of later forgers, this devious scribe, or chresmologue, started inventing his own prophecies and verses, interleaving them with Musaeus’s originals. Herodotus accurately states that when Onomacritus was inevitably caught—one Lasus of Hermione, a lyric poet, snitched—he was exiled to Persia where he simply continued his faux-oracular shenanigans, even urging Xerxes the Great to invade Greece. Which he did.

These days when people think of forgers, Lee Israel comes to mind, in no small part because of Melissa McCarthy’s riveting performance in Can You Ever Forgive Me? But compared to Onomacritus and William Henry Ireland and other high-stakes forgers of the past who manipulated the historic record in far more technically sophisticated, intellectually cunning, and ethically diabolical ways, Israel is a minor figure in an illustrious if corrupt pantheon of literary scammers.

Just as Ireland the forger was the son of Ireland the pundit, many accomplished forgers—most of them men—have been the children not of finaglers and fraudsters but of upstanding literary citizens in their day (or else absent fathers). The son of the now pretty-much forgotten poet Eugene Field, genial nineteenth-century author of children’s verse like “Wynken, Blynken, and Nod” and “Little Boy Blue,” would himself be entirely forgotten were it not for his being a prolific forger. And because Eugene Field, Jr. specialized in faking Abraham Lincoln documents, forging the president’s ownership autograph in books from his uncle’s library, today is he part of a large rogues’ gallery of Lincoln forgers.

After the president’s assassination in 1865 and well into the next century, members of this cohort of Lincoln “specialists” were busy reinventing honest Abe’s life and work. Their backstories are often so freakish as to seem unreal. Take Mario Terenzio Enrico Casalengo, an Italian immigrant who changed his name to Henry Woodhouse after being released from prison for manslaughter in upstate New York. Unbowed, he reinvented himself as a credible scientist, aeronautics expert, economist, historian. And forger.

Woodhouse—or Colonel Woodhouse, or Dr. Woodhouse, as he styled himself while ascending into higher echelons of society—produced fake Lincoln documents as well as missives by the signers of the Declaration of Independence. He even forged letters by his newfound friends Teddy Roosevelt, Amelia Earhart, and Alexander Graham Bell, to name a few. At some point Woodhouse decided to position his creations side by side with authentic materials—not unlike his ancient predecessor, Onomacritus—though he did so in order to sell them at Gimbels Department Store in Manhattan, not archive them in the repositories of the tyrant Pisistratus in Athens. And while he served time for killing a fellow cook (yes, he was a professional cook, too) and his illicit expertise was sometimes called into question, the good doctor Woodhouse was, astonishingly, never exposed as a forger during his lifetime.

Two Lincoln letters, one by Lincoln and one by the notorious Joseph Cosey, both dated 1863. (Alfred Whital Stern Collection of Lincolniana, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, The Library of Congress.)

If Abraham Lincoln has the unhappy distinction of being among the most forged of historical figures—maybe the most frequently forged of all—at least he attracted the best of the worst. Others famous for their first-rate simulacra of Lincoln documents are Harry D. Sickles (Field Jr.’s partner-in-crime), John Laffite (or Laflin—names are fluid in the forgers’ subculture), and the masterly if careless Charles Weisberg, who died in Lewisburg Prison in Pennsylvania, serving one of several sentences after being convicted on fraud charges. The ink he used in supposed Civil War documents was wrong for the era. He wrote lengthy Lincoln letters though Lincoln himself tended toward brevity. His last gaffe was to write an authorial inscription in Katherine Mansfield’s posthumously published The Dove’s Nest. You can, as a wise man once said, always get it right most of the time.

Arguably, the greatest of them all was Joseph Cosey. Born Martin Coneely in 1887, he ran away from home and led a solitary, shady existence as a small-time crook, living hand to mouth as he developed a taste for alcohol and phony Lincoln letters. Under the alias “Cosey,” he produced with legendary ease many thousands of unsurpassed forgeries of Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and Edgar Allan Poe. If you bought him a drink at a bar, he would knock out a masterful forgery for you on the spot; buy him another, get another. An unknown but likely considerable number of his forgeries remain unidentified to this day, reposing in private collections and temperature-controlled archives of institutions around the country, indeed the world. Some of them have even been unwittingly cited in biographies of Poe and others, perverting our knowledge of influential writers and historical figures, revising American history itself.

The mere mention of Cosey can provoke an apoplectic response from otherwise refined, mannerly collectors of 19th-century Americana. I’ve seen this fury first-hand and appreciate the exasperation of being deceived by Cosey even decades after his mysterious disappearance and probable death in 1950. To buy unknowingly an immaculate fake for the same money that an original fetches, only to learn later that it’s by Cosey, not Jefferson or Twain, is a vexing and expensive misstep. The most seasoned collector has at some point or another been duped, at least temporarily, by forgers nowhere near as sophisticated as Cosey. Myself included, details to follow.

*

Equal in skill to Cosey, but with an antithetical lifestyle and approach to forgery, was Thomas J. Wise (1859-1937), the well-liked, esteemed dean of book collecting in his day as well as an illustrious bibliographer—president of the Bibliographical Society, no less. His Ashley Library was among England’s finest in private hands, subsidized by his shrewd dealings as a behind-the-scenes bookseller. He also covertly printed severely limited editions of pamphlets by the likes of Tennyson, Kipling, Rossetti, and Swinburne, editing them together from genuine published texts, then falsely dating them earlier than their first editions. Any serious, completist collector of one of his counterfeited writers really had to add these manufactured rarities to their holdings.

Given what a precision craft forgery is, it’s intriguing that pride, precociousness, diffidence, depression, alcoholism, and a tendency to suicide feature in the lives of many of its finest practitioners.

Given Wise’s impeccable reputation in London and abroad, together with the fact that he catalogued his fakes alongside genuine first editions in his erudite, elegant bibliographies, the scheme was, for a long time, failsafe. When Wise personally offered a “newly discovered” Browning or Shelley or Ruskin to a prospective buyer, money usually passed hands and all involved were satisfied with the transaction. The British Museum was happy to pay the then-strong price of three guineas for a copy of his George Eliot pamphlet, Brother and Sister Sonnets by Marian Lewes.

This fall I visited Washington University in St. Louis to speak at the centenary celebration of writer William H. Gass. While touring the library I noticed there was an exhibit of forgeries on display. In one glass case I saw a pamphlet that looked for all the world to be Wise’s Brother and Sister Sonnets. But here was a fake of a fake—strange as some two-headed calf, I remember thinking as I peered at it through the glass. Amazingly, I’d encountered a later fabrication of Thomas J. Wise’s original forgery from 1888 (which Wise had backdated to 1869 on the cover and title page, designating it “For Private Circulation Only”).

Surely Wise might never have guessed that, years later, some obscure American forger would decide to counterfeit his counterfeit. They look—as good piracies are supposed to look—alike. The only way to tell the difference, as the curator of rare books, Cassie Brand, noted while touring me through her selection, is that the later “creation. . .used a fleuron on the corners of the cover and left out the horizontal line at the end of the text.” Without that devilment of a detail, none would be the–

Wise was run to ground in 1934 by an intrepid pair of young rare book dealers, John W. Carter and Henry Graham Pollard, who published their shocking landmark bibliographic investigation, An Enquiry into the Nature of Certain Nineteenth Century Pamphlets, three years before Wise died. While the authors never explicitly accused him of wrongdoing, controversy swirled around him and he went to his grave denying any involvement.

*

Given what a precision craft forgery is, it’s intriguing that pride, precociousness, diffidence, depression, alcoholism, and a tendency to suicide feature in the lives of many of its finest practitioners. While some are gregarious, like Wise, and others reclusive, like Cosey, most major forgers possessed the intellect, creativity, and energy to have pursued legitimate careers as historians, poets, professors, and the like, socially negotiable but for one countermanding trait. In some way or another, all forgers—even those who create fakes to make ends meet—share a compulsion to outwit experts and outmaneuver authorities.

The elite among them try to transcend accepted reality, nudge their bizarre way into the known, be a player in history from a skewed and illegal angle. The genius of an authentic writer dovetails with, and is temporarily subsumed by, the forger’s own genius. With a defiant, willful, and full flowering of hubris, they aspire briefly to become the very person they forge. It is an intoxicating enterprise, this fusion of imagination and chicanery. A white collar (or ruff, as the case may be) crime as sophisticated as it is deplorable.

It is also, largely, doomed. Just as most deceits eventually unravel, most forgeries sooner or later are identified and exposed. Examples abound. In one recent case, a Galileo document dating from 1610, with historically groundbreaking sketches and notes depicting the orbits of Jupiter’s moons, resided at the University of Michigan Library for a century before being outed in August 2022 as the work of the infamous 20th-century Italian forger Tobia Nicotra. Following extensive research into the document, focusing on a telltale watermark of the paper used by Nicotra, the library announced that their once-priceless “jewel” was a fake and, as a result, the revisionist history of Galileo prompted by this manuscript required yet another revision.

True first edition of Aldine’s Dante (1502) . (Courtesy of Sotheby’s, New York.)

The Lyon forgery (circa 1503).(Courtesy of Sotheby’s, New York.)

While one might reasonably assume that all such proven forgeries would instantly lose their value, be relegated to the category of worthless curiosities, this is not always the case. Indeed, some counterfeits and forgeries are collectible in themselves and even boast values similar to the originals. In the Sotheby’s October 18, 2024 sale of books from the magnificent Renaissance library of T. Kimball Brooker, an authentic 1502 copy of Dante’s Le terze rime—the Divine Comedy—one of eight known copies printed on vellum in Venice at the Aldine press, beautifully illuminated, brought $165,100. Several lots later, the Gabiano-Trot forgery of the same book printed on vellum just a year or so after in Lyon, France—the first edition of Dante ever printed outside Italy—was hammered down at a competitive $158,750. The intrigue behind Lyonese Aldine counterfeits is the stuff of legend, and in the history of intellectual property theft it is hardly surpassable for prowess, guts, and mendacity.

*

Were there a Forgers Hall of Fame—or, Infamy—influential sleight-of-handwriting artists would certainly include the precocious, deeply troubled Thomas Chatterton (1752-1770), who committed suicide in London by overdosing on alcohol at age 17, but not before brilliantly forging the spurious, inspired “Rowley” poems that would have a major impact on the Romantic poets Coleridge, Wordsworth, Keats, and Shelley. Scottish poet, politician, and collector James MacPherson (1736-1796) claimed to have discovered and translated a Scottish/Gaelic epic from the third century by a Bard named Ossian. Though the subject of withering attacks of critics like Samuel Johnson who claimed the “Ossian cycle” was a fraud, MacPherson’s forgery proved popular and is credited, for worse or better, with helping to fashion Scotland’s national self-image.

It is safe to say that many if not most university or public libraries of any size could mount a similar exhibit of literary forgeries as compelling as the one in St. Louis.

The list is long. Denis Vrain-Lucas forged and sold over 25,000 documents beginning in 1854, including “original” letters from Cleopatra, Isaac Newton, Attila the Hun, Mary Magdalene, Pontius Pilate, and even the resurrected Lazarus—all in French. Alexander “Antique” Smith, a Scottish law office clerk turned forger in the 1880s, cranked out a vast number of “unpublished” letters and poems by Burns, Scott, and Thackeray. Robert Spring migrated from England to America, erased his past, and set up an antiquarian bookshop in Philadelphia where he commenced forging payment orders and letters by George Washington and others. He was arrested, fled to Canada, returned to America, leaving a trail of fake documents in his wake until he was apprehended again, confessed, and died in prison. Like Cosey and Wise, Spring now has the distinction of being collected in his own right as an upmarket forger whose work, whether or not identified as fake, is no doubt held in the archives of prestigious collections.

It is safe to say that many if not most university or public libraries of any size could mount a similar exhibit of literary forgeries as compelling as the one in St. Louis. Even my own book collection includes a problematic copy of the 1919 first English edition of Joseph Conrad’s The Arrow of Gold, with an elaborate armorial bookplate of Baron Leverhulme of Bolton-le-Moors, whose engraved insignia of a cock and rampant elephants lends it an impressive air of authenticity. Laid in is a clipping from an early bookseller’s catalogue offering this copy as having “Conrad’s autograph signature below his printed name on the title page.”

Yet despite its persuasive provenance and expert assurances, despite its signature appearing to be contemporary and confident in its execution, my signed Conrad is surely a forgery. Many details of the autograph seem wrong, beginning with the shapes of the initial letters of his name along with an overall studied appearance—overly careful, deliberate, antiseptic, and simply misshapen. Fortunately, when I acquired it at auction, the lot included another first edition of Arrow in superlative condition, which was the one I actually wanted. To their credit, the auction house listed the signed copy as possibly spurious.

The authoritative provenance and early bookseller’s assurance of authenticity (left) and the sad truth (right). (Author’s collection.)

Some years later, two Cormac McCarthy rarities I acquired from a highly respected auction house in London were so cleverly wrought that they fooled both the firm’s seasoned cataloguer and me, an experienced collector and sometime dealer. I had never before seen proof copies of the British editions of McCarthy’s early novels Outer Dark and Child of God, so I went for broke and outbid others anxious to get them. They arrived, clearly uncirculated and pristine, and after cataloguing them, I gingerly put them on my shelf with other McCarthy firsts. Alas, several months later I received an email from my friend at the house, apologizing as he told me they were forgeries. The design layout, the covers, the text itself were cleverly cobbled together. Even though it came out of a prominent collection belonging to one McCarthy’s own friends, it was wrong as rain.

*

Picasso once remarked that “Good artists copy. Great artists steal.” Forgers do both. And whether we think of them as twisted imitators, diabolical artificers, antiauthoritarian heroes, or whatever else, it is reasonable to believe that they will continue to cast shadows where legitimate writers tread. As E.K. Chambers long ago suggested, those of us who value originals over fakes will ever owe gratitude to the Lasus of Hermiones, Edmund Malones, Carter and Pollards of the world for revealing the truth. After all, the history of literary forgery is still actively being made. More than one bookseller friend of mine is even now involved in exposing brazen forgeries of iconic modern writers.

Veteran rare book dealer Ken Lopez, just for instance, was asked by a client to authenticate Cormac McCarthy’s signature in a previously unrecorded proof copy of Outer Dark. With the help of his assistant, photographer Brendan Devlin, they caught “telltale inkjet color spots” on the proof and through a combination of technical scrutiny and decades of expertise, both proof and autograph were declared fakes. As Lopez wrote to me, with typical modesty, “It was just a matter of looking and paying attention.” What followed was the discovery of a massive cascade of far-flung forgeries meant to alter both McCarthy’s bibliography and biography. An impressive “Illustrated Edition” of Blood Meridian was even in the works. Thanks to Lopez’s “paying attention,” a collaborative pair of ambitious McCarthy forgers, whose methods were akin to Wise’s, was exposed.

Sophisticated McCarthy forgeries of British proof copy and illustrated Blood Meridian. (Photographs by by Brendan Devlin. Courtesy of Ken Lopez.)

This kind of ongoing work represents just the kind of erudite, diligent, passionate investigation that will bring forgers to heel at least most of the time. For, as long as writers write and forgers forge, there will be astute, idealistic book sleuths—often book dealers, auction houses, and librarians—shining true light into devious shadows. Indeed, on the very day I finished writing this piece, I attended online an auction taking place in Texas, where the first edition of H. P. Lovecraft’s ultra-rare first book, The Shunned House, was listed in the sumptuous print catalog of the William A. Strutz sale. But when the auction went live, I noticed the internet listing had been revised: “*Note: This description has been amended, and the references used have been updated. The present copy is the 1965 forgery as described by Joshi.” Unbeknown to one of the great collectors of his generation, The Shunned House had resided in a place of honor, shelved between Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Amy Lowell, for decades before a sophisticated auction cataloger flushed it out as a fake. Even at that, however, it was hammered down at well over a thousand dollars. And so it goes.

*

The author is grateful to Janet E. Gomez whose essay in Fakes, Lies, and Forgeries (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 2014) was crucial to my research on Henry Ireland. Thanks also to Selby Kiffer and Fenella Theis at Sotheby’s, Cassie Brand at Washington University Library, Hannah Elder at Massachusetts Historical Society, Michael North at Library of Congress, and Ken Lopez, for their time and expertise.

____________________________

Bradford Morrow’s The Forger’s Requiem is available now from Atlantic Monthly Press.