All images courtesy of the author.

For the past decade, the “Ghost of Reem Island,” as she was referred to in the press, has haunted me.

On December 1, 2014, Ala’a al-Hashemi, a Yemeni-born Emirati woman, murdered a Hungarian American schoolteacher in a public restroom in Abu Dhabi. The media cited the incident as a “lone act of terror.” I too was an American teaching in Abu Dhabi and, by a bizarre coincidence, had been spending an inordinate amount of time in public restrooms, photographing female bathroom attendants for a creative research project.

More than ten years after the murder, I still find myself sifting through the little that was left behind—the government search-and-arrest video that went viral, news articles chronicling the political landscape of the time, and my own photographs of bathrooms and their attendants.

***

In 2010, I was sitting in my office at NYU, where I teach in the film department, and knew something had to change. I’d been trying to secure financing for a feature film, actors had attached and then dropped out, and I was gripped by a sense of inertia and myopia; I wanted to be engaged in a larger conversation with the world. Around that time, I received a phone call from the dean of the College of Arts & Science, telling me that I’d been selected to serve on the committee for an exciting new project: NYU Abu Dhabi. “An international honors college, a Swarthmore in the desert.”

I only vaguely knew where the United Arab Emirates was on a map.

Thanks to a partnership with the UAE government, the venture was well funded. The forty-acre campus of twenty-nine buildings would be built in the cultural district on Saadiyat Island, soon to be home to the Louvre, Guggenheim, and Zayed National Museums. So much of academia involves splitting hairs over a pittance of funds, but this, I was told, was a unique opportunity to reimagine the university for the twenty-first century from the ground up: an expansive and bold vision predicated on an international student body and a global approach to learning that promised to erase the barriers between disciplines. The Arts Center and the Science Center would sit side by side, cross-pollinating and informing large research projects.

I was asked if I’d consider working on the Abu Dhabi campus, and flown out to the UAE for an exploratory visit. It was my first time flying business class and upon boarding, I was handed a mimosa, black pajamas folded into drawstring bags, and a menu printed on ivory cardstock; I marveled at the airplane bathroom with a shower. Upon arrival, I visited the fledgling campus, walked the superblocks, and explored the honey, pastry, and stationery stores. At the Emirates Palace, I ordered a gold-leaf latte and toured the heritage village exhibits on falconry and pearl diving. At sunset, I cycled along the corniche where I was told I could see the shores of Iran on a clear day.

Eventually, I agreed to take the job; to teach and serve as the associate dean of the arts, overseeing working groups of artists and scholars ideating new approaches to film, theater, music, photography, and technology that would marry theory and practice.

I commuted the seven thousand miles every six to eight weeks. My kids were seven and nine. At the baggage claim in Abu Dhabi, a colleague said to me, “I could never do what you’re doing.” There was judgment behind her self-deprecation, and I started to avoid her on campus. Every time I left my kids crying on the curb in my husband’s arms, I questioned my choices.

But the work was heady and exciting, a time of Moleskine notebooks and endless to-do lists, bottled water and back seats of town cars, business class flights on Etihad, hotels and guest apartments, blueprints unfurled across tables and 3D models revealed with fanfare, interviews with artists and scholars, and reading Appiah, Said, Amin Maalouf, Naguib Mahfouz, and Assia Djebar.

Prospective students were recruited from around the world and underwent a rigorous admissions process that promised free tuition to those accepted. Our first class had a hundred and thirty students from forty different countries. At the center of NYU Abu Dhabi is its stated mission to “welcome and educate global citizens, and produce knowledge in order to promote human understanding and to better society …”

But it was also a time of large museum projects, labor infractions, and NYU faculty in New York expressing concerns about the vision of the “global university” and academic freedom at our emerging campuses in Abu Dhabi and Shanghai. The regional turmoil in the wake of the Arab Spring and soon the arrests of activists, lawyers, professors, and students in the mass UAE94 trial would hang over the project. ISIS would be on the rise, the U.S. would bomb Iraq and Syria, and oil prices would be crashing.

After two years, the commute was no longer tenable for our family, and we decided to move to Abu Dhabi on a two-year contract. Our farewell to the States was emotional and chaotic.

We moved into an apartment on the thirty-fourth floor of a high-rise overlooking the Arabian Gulf.

And some mornings, we woke up inside a cloud.

***

One of the first places I visited in Abu Dhabi was the Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque. Completed in 2007, the mosque incorporates Persian, Mughal, and Indo-Islamic traditions and serves as a beacon of tolerance that can host up to fifty thousand visitors. Reflective pools, the expansive marble courtyard, inlaid tiles, minarets, and the largest hand-knotted carpet in the world inspired awe, but it was my trip to the bathroom that left the deepest impression.

A circular ablution area, bathed in sunlight from the glass dome above and made from white and green marble, greeted me at the bottom of the stairs. Stone-and-marble stools circled the green basins and metal faucets used for wudu, the ritual washing before the recitation of prayers.

In the ladies’ room, I was struck by a sense of safety and international female camaraderie that reminded me of the Dubai airport, a global crossroads that feels like the capital of the world, a hub that embodies and holds our human connection as we pass one another on the concourse, order coffee, and wait at the gate. In the bathroom, women from Pakistan, France, and Jordan exchanged greetings at the mirror. The bathroom attendants, both from South Asia and on two-year contracts, cleaned the stalls, stocked supplies, and provided a sense of protection and care. When I asked if I could take the attendants’ picture, they wrapped their arms around each other and posed in front of the botanical tiled wall.

The first photograph I took in a women’s bathroom.

Across the UAE, prayer rooms and bathrooms live side by side, and this pairing of the sacred and the profane was my favorite aspect of the built environment, an acceptance of our flawed humanity and our desire to purge, wash, and dedicate ourselves, once again, to do better.

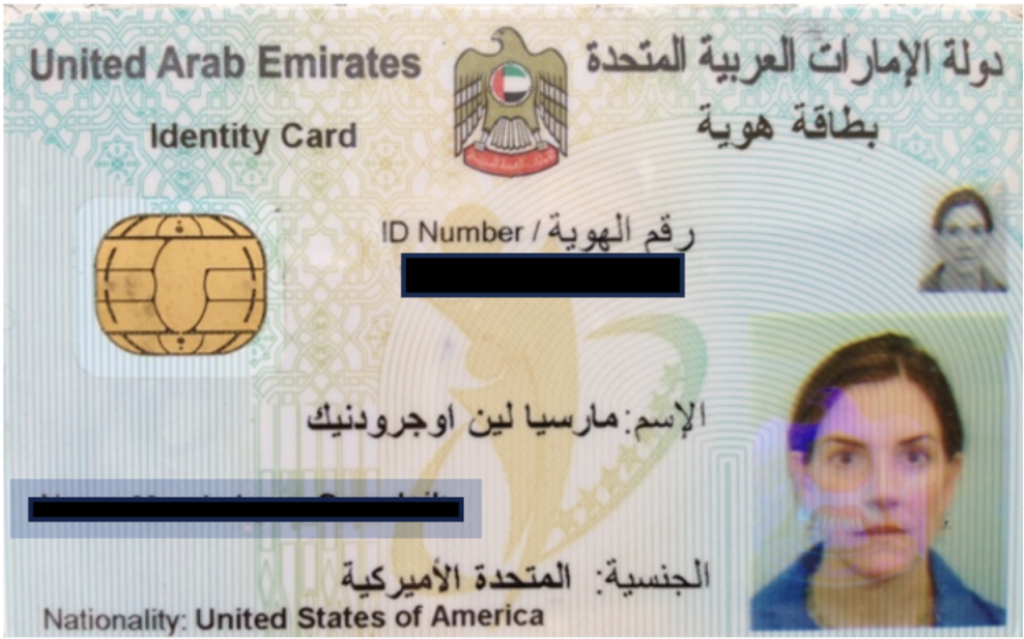

The UAE has one of the highest concentrations of surveillance technology in the world, and I was aware of the chip in my identity card and the rumors of the government listening to phone calls and tracking locations. The wide and shadeless boulevards left me feeling overexposed, fading in the heat, and public restrooms offered pockets of shade and human connection.

My excursions to malls, bus stations, and parks to photograph bathrooms and bathroom attendants fed my desire to push beyond the proscribed lines of my experience as a foreigner into something authentic. These bathrooms became places of intimate exploration—windowless public spaces beside the prayer rooms that were not surveilled.

Prayer room, Sharjah bus station.

The bathroom attendants often had children back home in Kerala, Colombo, Lahore, Manila, Addis Ababa—and while many of them lived in labor camps and worked for large companies, their workplaces were private. The bathrooms were their offices, their spaces to monitor and take care of; I was the visitor.

I don’t remember much about the Sharjah International Book Fair or the Rolling Stones concert in Abu Dhabi, but I do remember the attendants and their bathrooms.

All the women I spoke with were working in the Gulf to send money home to their families, to save for a house, school, or medical bills. As they shared their longing for home, my own loneliness found theirs, and I often thought of my own mother, seven thousand miles away in an assisted living facility in Maine.

Maybe these encounters brought me back to the pink slips and bathroom passes of my girlhood: whispers with friends in graffitied stalls, tears at the mirror, and spanning time on tiled floors beneath frosted glass windows and throwing wet paper towels against pockmarked ceilings.

Or the bathrooms in the homes of friends, portals into the private lives of grown-ups. Parents who painted their bathroom black, attached glow-in-the-dark constellations to the ceiling, and enjoyed the night sky from a claw-foot tub with a stack of wrinkled Playboys within reach.

Or the en suite bathroom that belonged to a friend’s parents who were a doctor and nurse. We had to cross their bedroom, past the sprawling king-size bed with taut sheets, to use the toilet. Their bathroom, with rough towels, mustard-tiled walls, and glass bottles filled with soap and shampoo, and, in the medicine cabinet, only aspirin, Band-Aids, and Neosporin. No lipstick, blush, or lotions—just the necessities—an unsettling medical efficiency that left me feeling chastened.

I’ve always been curious about people’s medicine cabinets; I like to snoop through their lavatory supplies, to discover their secret ailments, their chosen creams, the scents they use to augment and camouflage their smells. The bathroom, where our animalness lives.

When I was eight or nine, I had my tonsils taken out and tubes put in my ears. I returned home from the hospital with a fever and stood naked beside my mother as she drew me a bath. My hearing was restored, and the sounds of water gushing from the faucet, the pouring of Epsom salts from the box into the tub, and even my mother’s voice asking me to undress, brought me to tears. My mother bathed me with a washcloth as red dots appeared on my arms, legs, and stomach. “Chicken pox,” she announced. “No wonder you have a fever.”

***

It is December 1, 2014, the eve of National Day in the UAE. My family has moved back to New York City, but I’ve returned to Abu Dhabi to host an academic conference exploring the narration of national identity by scholars and artists in the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia.

The UAE defines itself as a progressive Arab nation of the twenty-first century. Emirati citizens comprise only 11.5 percent of the country’s population and much of their labor comes from guest workers, white collar and blue collar, living in labor camps, high-rise apartments, or in gated communities, all working on multiyear contracts to build and support the country, a nation vigilant in protecting its borders from extremist groups. Shia mosques have recently been bombed in Saudi Arabia, and the UAE is hosting U.S. military personnel taking part in military campaigns against Islamic State groups and Shiite rebels in Yemen.

Tomorrow, the country will celebrate forty-three years of independence from the British protectorate, with parades, fireworks, and dancing. Today, I learn that an American schoolteacher has been murdered “in an act of terror” in a public bathroom out on Reem Island, an island I’ve never visited but is only a fifteen-minute drive from campus. I have colleagues who live there. In the guest apartment, a loaf of bread, a carton of eggs, a stick of gold-foiled butter, and a liter of milk welcome me home. The cold tile floors send me in search of socks, and I shut off the air-conditioning and open the windows into the desert night.

Less than forty-eight hours later, the assailant is apprehended, and a barrage of text messages from colleagues alert me to the UAE government YouTube video documenting the police arrest of the “Ghost Killer.” I search the closet for extra blankets and burrow into one of the twin beds with my computer. The video is not hard to find. Already, there are 8,072,198 views. 31,923 Thumbs Up. 5,110 Thumbs Down.

I press play.

***

FADE IN:

The green-and-gold falcon crest of the United Arab Emirates fills the screen and the theme music of THE DARK KNIGHT RISES propels us into the action.

This is a state-sanctioned video sending a message to its citizens and the world: We do not tolerate terrorists, you are safe. But the Batman soundtrack skews the video toward entertainment and I feel uneasy.

INT. MALL PARKING GARAGE – DAY

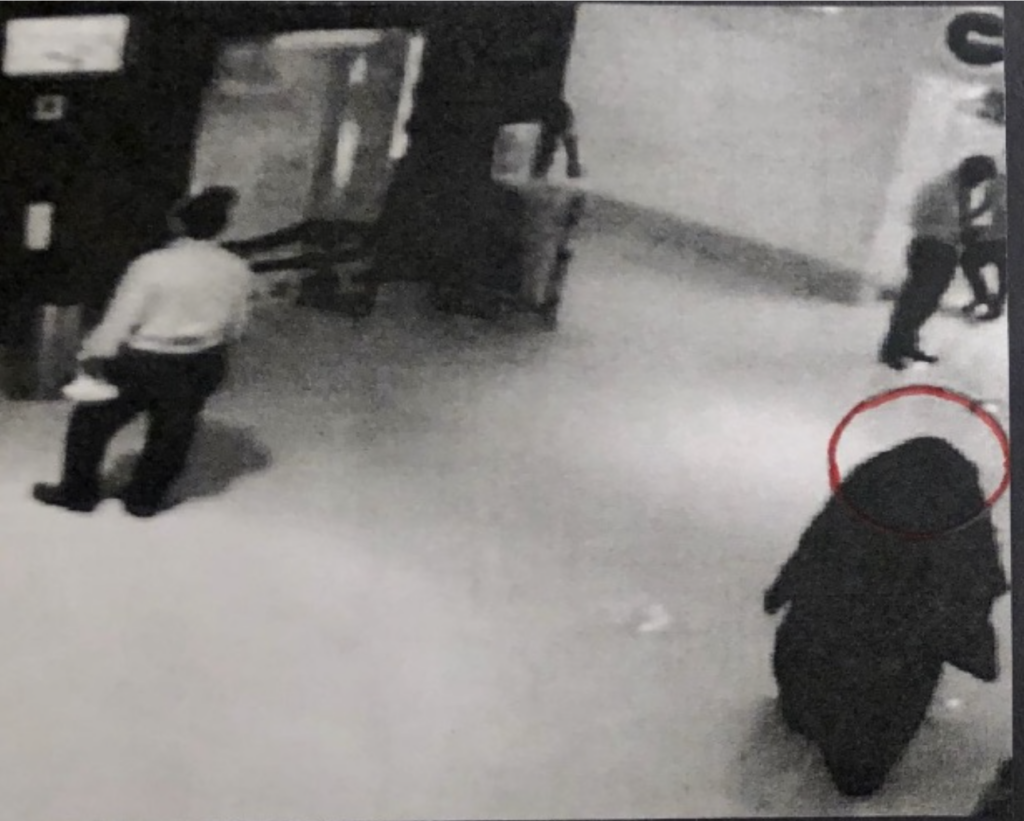

HIGH ANGLE – CCTV FOOTAGE:

A SECURITY GUARD stands in front of glass doors leading to the elevator bank. He welcomes a WOMAN dressed in a black abaya, a black niqab, and black gloves. She has a square build, a lumbering gait, and she carries a large purse on her shoulder. They nod in mutual acknowledgment as she passes.

The WOMAN pushes the elevator button and regards two large standing posters as she waits.

The poor image quality obscures the posters, but it looks like an advertisement for YAS WATERWORLD and I imagine bikini-clad girls careening toward the camera.

Yas Waterworld—a place of manufactured fun in the middle of the desert, a place I’ve endured for our kids when all other forms of entertainment failed. A place where I camped out on lounge chairs with my books, surrounded by water slides, chemical-blue pools, the garrulous screams of children, while couples sip slushies out of neon plastic cups after a float down the “lazy river.” The smells of fried food and coconut oil mingle with the piped-in music of Rihanna, Beyoncé, and Pharrell Williams—“Happy.”

The elevator arrives and the WOMAN disappears inside.

INT. MALL – CONTINUOUS

The WOMAN emerges from the elevator. She ignores the other shoppers and moves into the foreground to speak with a security guard, who points her down a hallway.

I suspect she’s asking for directions to the bathroom, but she must have scoped out the location for the murder. Perhaps this is strategic—she’s talking directly to the security guard in order to avoid suspicion later. This worked for me when I stole things as a teenager.

The WOMAN grabs a NEWSPAPER from a rack before disappearing around the corner.

We’re left watching a round-bellied man with a beard, a lanky worker in a blue uniform, and a South Asian woman waiting for the elevator.

FADE TO BLACK

Because there are no surveillance cameras in the public restrooms, there’s a ninety-two-minute gap in the footage when the murder takes place. The media reports that she waited for over an hour in a bathroom stall to pick her victim. I wonder if she looked at the newspaper during that time. Perhaps it calmed her nerves to read about the street closures for the National Day parade, about the decreasing cases of Ebola, about Yazidi girls training to take on ISIL, or about how Emirati women took up arms against the British in the early 1800s. The weather was 25 degrees Celsius and sunny. Maybe grabbing the newspaper provided some kind of comfort, like a blanket across her legs while she was waiting. Planning. Maybe she used the newspaper to hide the knife.

I imagine she was worried about her six children.

Or perhaps she was thinking about her husband, who’d been taken from their house in the middle of the night for questioning and had not been seen since. Months after her arrest, he’ll be charged with plots to bomb the Formula I racetrack and IKEA. He had made plans to kill tourists and assassinate a local leader. It will also be reported that Ala’a had visited Al Qaeda websites and had given the organization money in Yemen. The Guardian speculated that her husband’s disappearance had stoked her fanaticism and compelled her to act alone that day.

Apparently, she decided against a British woman who came into the bathroom with a child in a pram. Someone told me that, but I don’t know how we would we know that kind of detail. Perhaps it was something she told the press.

I wonder what it was about the teacher that caused Ala’a to choose her. The “ghost” asked for help getting into the handicapped stall and the teacher obliged. A witness heard a woman say, “Be quiet or I’ll kill you.” Ibolya Ryan’s willingness to help led her into the stall, a stall reserved for the physically vulnerable. Ala’a manipulated the social contract between women to kill her victim.

Meanwhile, Ibolya Ryan’s eleven-year-old twin sons waited for their mother at a café. When their mother did not arrive, they decided to walk home to their nearby apartment. I imagine their fear, that liminal place of dread, between not-knowing and knowing, the weight and volume of impending catastrophe.

Someone reported the SOUNDS of SCREAMING and STRUGGLE as the teacher was stabbed to death with a carving knife.

Perhaps the bathroom attendant at the Boutik Mall on Reem Island was on her lunch break at the time of the murder. If she’d been present, surely she would have noticed a woman camped out in the handicapped stall for over an hour. Concern would have ceded to suspicion. I want to believe the crime could have been thwarted.

The bathroom attendants I interviewed during my time in Abu Dhabi felt ownership over their bathrooms. While they may have been invisible to many of the women who used the facilities, they were aware of every woman who arrived and departed.

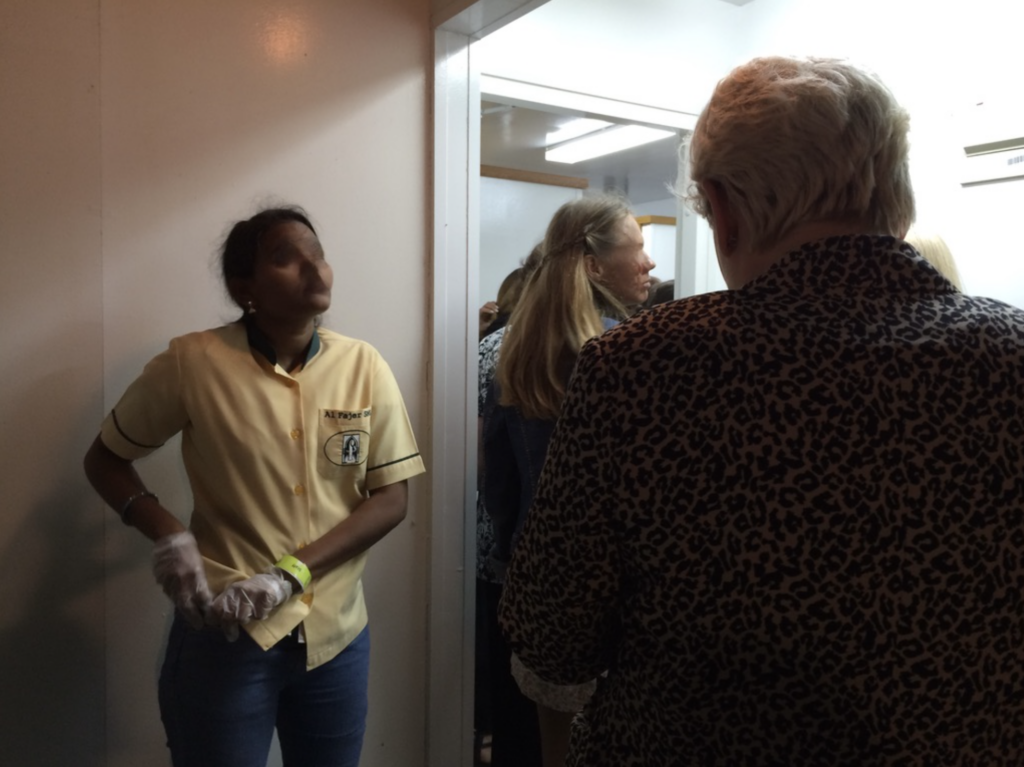

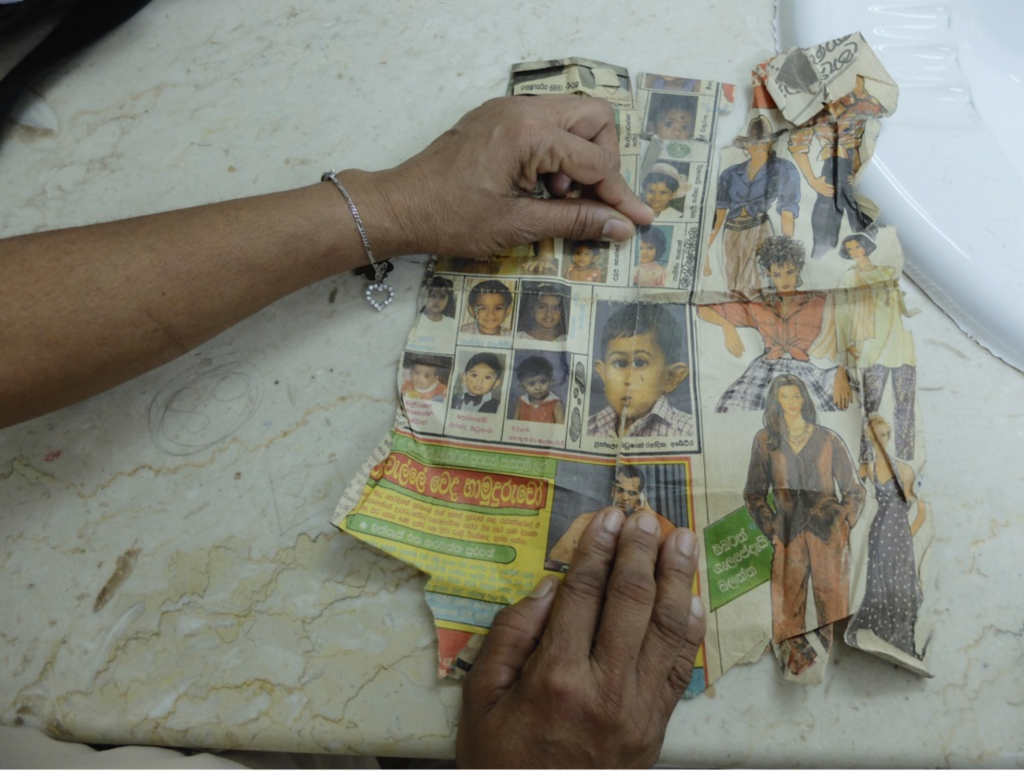

This photograph was taken at Marina Mall, in a hidden-away bathroom on the ground floor.

The attendant pulled out a worn newspaper clipping that featured her child and asked me to take a picture. The crease in the newspaper was torn and frayed from the many times she’d reached for her son and refolded him into her pocket.

For this picture, the woman asked to change out of her sneakers and into her “day” shoes. In the storage closet across from the shelves of toilet paper and glass cleaner, she’d taped a photograph of her daughter playing the piano at her second birthday party to the wall.

All these mothers and children, separated by distance. Now, with this crime, nine more children have lost their mothers.

***

SURVEILLANCE FOOTAGE: ELEVATOR BANK

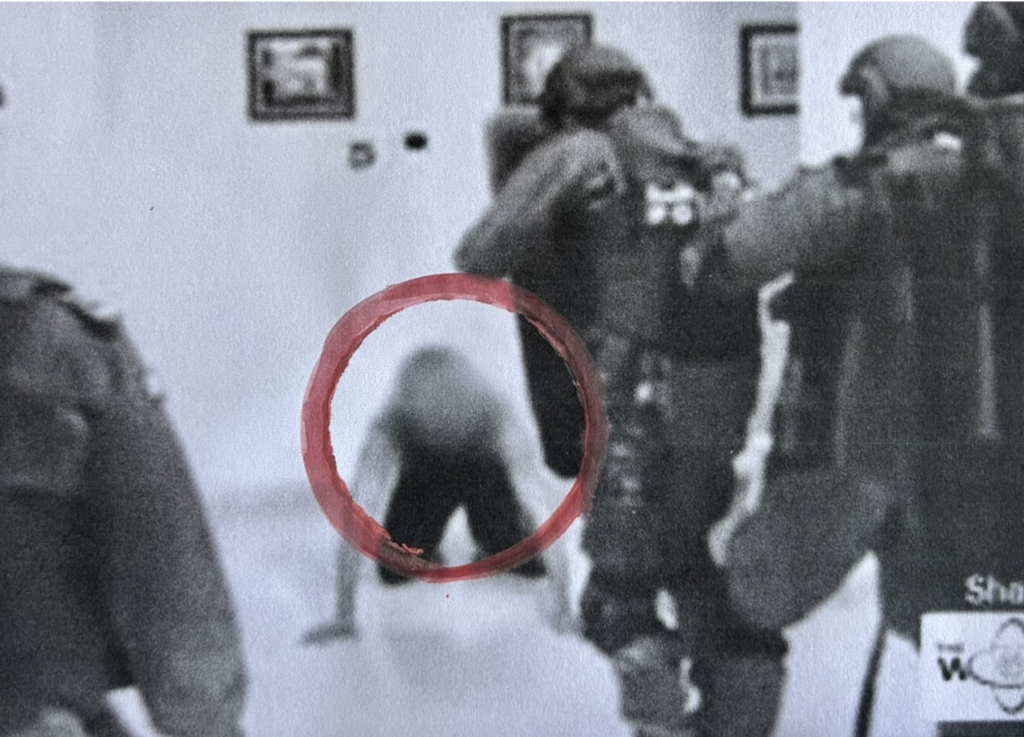

The WOMAN, circled in red, is on the move, and shoppers get out of her way. A mother grabs her son’s hand and disappears into Bath and Body Works. A woman in a headscarf tries to block the WOMAN from getting on the elevator and calls for help. In the corner of the frame, a man in a kandura looks at his phone.

The WOMAN steps into the elevator. The doors close as a man dressed in black lunges at the buttons.

EXT. MALL PARKING GARAGE – CONTINUOUS

The WOMAN swings through the glass doors and heads toward her car.

EXT. STREET – CONTINUOUS

A white SUV with a National flag draped over the back window heads down the street.

EXT. APARTMENT BUILDING – DAY

The WOMAN walks toward an apartment building, pulling a black suitcase behind her.

During the nineteen-minute gap in the CCTV footage, she plants a pipe bomb at the doorstep of an Egyptian American doctor. The bomb never goes off.

EXT. PARKING LOT – NIGHT

A handheld camera moves through a group of police officers. We see police cars, flashing lights, men in reflector uniforms, men in kanduras.

CLOSE-UP: HANDMADE BOMB

Tape secures a rectangular device, maybe a phone, to a tube. It looks like a poorly bandaged limb in a child’s game of war.

A SERIES OF SHOTS ACROSS A TILED FLOOR: blue plastic bottle caps, white straws, red confetti, UAE flags on toothpicks.

I’m confused by this shot and these items and am not sure what I’m looking at.

EXT. PARKING LOT – CONTINUOUS

The camera circles POLICE OFFICERS listening to a man in a white kandura. The police are dressed in green uniforms, bulletproof vests, and magenta berets. Another man in a kandura stands with his hands clasped in front of him. The faces of the two men in kanduras are blurred out.

EXT. HIGHWAY – NIGHT

Police cars head into the night—red lights flashing to the rising orchestral score of THE DARK KNIGHT RISES.

INT. POLICE CAR – CONTINUOUS

CLOSE-UP on MEN’S FACES: serious and intent.

EXT. HOUSE – NIGHT

The SWAT team pushes through the iron gate and divides in half, left and right. The men head up the driveway toward the nondescript McMansion—guns drawn.

INT. HOUSE – CONTINUOUS

The police storm the house. The floors and hallways are bare, without rugs or much furniture.

I pause the video to inspect the paintings and photographs on the wall, but they’re too blurry to decipher. I’m desperate to know what they are, to gain some insight into this woman and her family life.

The officers surround a woman in a black tank top and leggings. She kneels on the floor, her face blurred—the Ghost Killer? She’s pushed to the ground where she’s hand-cuffed.

INT.. FOYER – CONTINUOUS

Another WOMAN drapes a tablecloth over her head to hide her identity as she’s escorted out of the house and into a police car.

MONTAGE: POLICE SEARCH

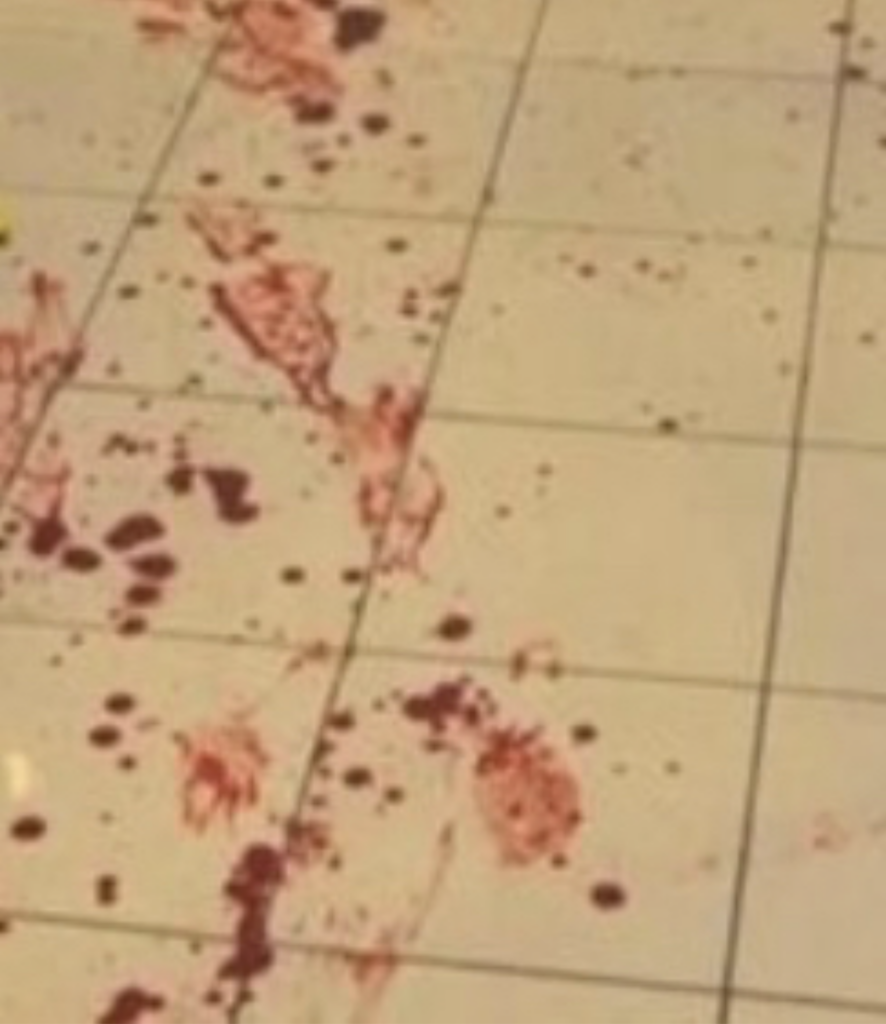

The music, its pulsating strings and beat, builds to a climax as we watch the police officers scale an outside ladder, kick open closet doors, and tip over empty cardboard boxes. We see a series of shots: a bloody steering wheel, bleach, and walkie-talkies.

I think of her six children. In seven months, their mother will be charged with terrorism and executed by firing squad.

EXT. HELICOPTER – DAY

We sweep above the skyscrapers of Abu Dhabi, the Arabian Gulf below, the UAE flag fluttering in the wind.

CREDITS: United Arab Emirates, Ministry of Interior

***

I close my computer and sit in the dark. Outside, the sodium-vapor lamps of the campus catch the leaves of newly planted palm trees. It’s quiet and empty along the walkways, no insect chorus or fireflies. I go to the bathroom. The light flickers above a bar of unwrapped soap and a thin towel, white and folded, on the toilet seat. The smell of chemicals and disinfectant roils my stomach. This act of terror committed in a bathroom stall fills me with dread. The crime expresses inherited and shared histories; reducing Ala’a to a ghost serves no-one.

I slip between the covers, where my mind churns through the night toward dawn. Just as Ala’a is not a ghost, Ibolya is not just a victim. Ibolya Ryan was born in Romania and grew up in Hungary. She was a woman, divorced, with two twin sons living with her in Abu Dhabi and a daughter residing in Europe with her ex-husband. Years later, I’ll discover a photograph of her family online, taken not long after the murder. The three children sit, awkward and hollowed-out, on the couch beside their father. One son grasps his sister’s hand as his head sinks into her shoulder.

***

***

I grew up in an old house in the Berkshires with my parents and grandfather. We shared the bathroom at the top of the stairs, a room with a low window that overlooked five crab apple trees and a driveway where my grandfather would sit, silent, in a wooden folding chair for hours. There was no shower, only a bathtub that we were required to clean with a sponge and Comet after each use. We revealed our private lives through a handful of intimate objects—my grandfather’s dentures soaking on the sink at night, his black-and-yellow box of Preparation H, my mother’s Valium, baby powder, and pink bath pillow, my father’s steel razor, Barbasol shaving cream, and Old Spice deodorant, my sanitary pads hidden beneath the sink, a palette of blush leftover from a display at my pharmacy job, the scale that weighed our bodies, and the towels that dried them. Tender and tidy offerings of ourselves comingled in this room at the top of the stairs.

Everyone in the house was afraid of my father, how humiliation and fury could take possession of him and last for days; a thick haze that left us isolated, without our bearings, wondering whether it was day or night. This bathroom at the top of the stairs held our bodies, our sexuality, our sickness, the nakedness of the family that no one shared. The twinning of intimacy and violence, larger histories and pain, earaches and water bottles, bandages wrapped around swollen limbs, cuts and the sting of peroxide, splinters and tweezers; all our filth and attempts at cleanliness and healing resided in the silence of that room.

***

When I lived in Abu Dhabi, I felt on the outside of another people’s history, a witness to a National Day that was not my own. But like Ibolya Ryan and Ala’a al-Hashemi, like the bathroom attendants from India, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh—I am here, stranded on the threshold of these bathrooms, scanning the hand soap, toiletries, and counters, the mirrors, toilet paper, and towels, angling toward something still out of reach.

Mo Ogrodnik is a filmmaker and professor at New York University. Her first novel, GULF, is forthcoming from Summit Books/S&S this May.