Photos by Laurence von der Weid.

Article continues after advertisement

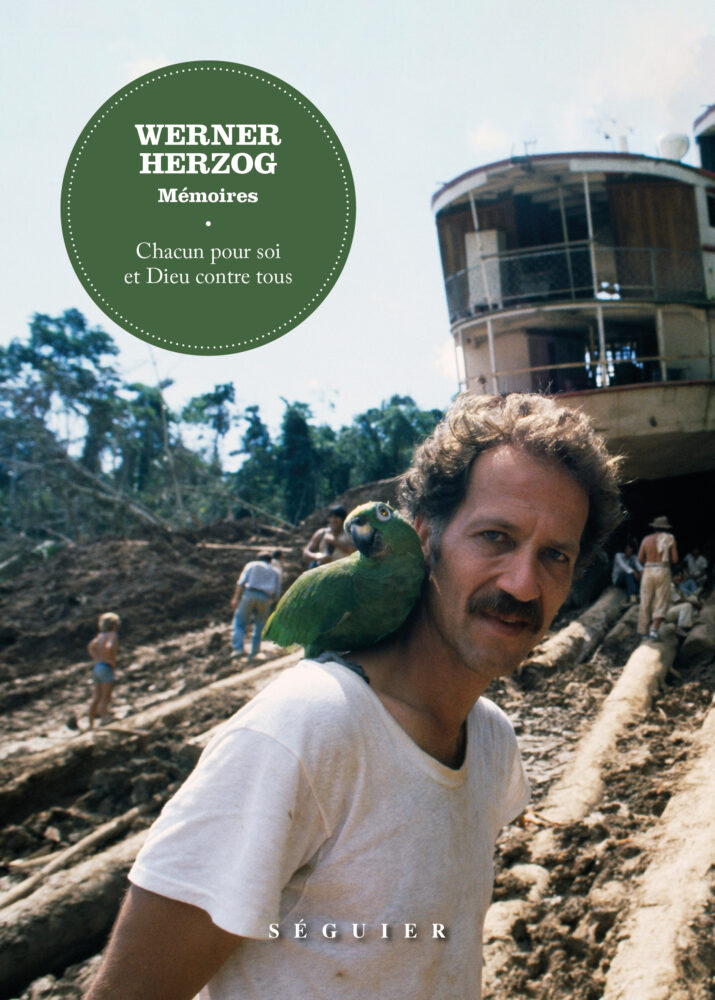

One thing is clear from the get-go: Werner Herzog, the enigmatic German icon of all things Art, likes for things to be precise. He makes sure I know this within the first minutes of our meeting. He is in Paris for48 hours for the release of the French translation of his memoir Every Man for Himself and God Against All, he has no time to waste, and surely less so at age 82.

Werner Herzog has written, produced, and directed eighty films, worked as an actor, staged operas, and written books. You can find him in the Congo, Peru or Greece, Mexico or Alaska; he traveled to rainforests, caves, and the edge of a volcano on the verge of eruption. This afternoon, however, he is sitting across the table from me, at the small dining area of the Parisian hotel he is staying at, glaring with eyes that hold a mix of madness, clarity, and freedom.

Before I even pressed record on my tape recorder, Herzog said: “I don’t want to talk about my films.” I admit hearing that from a man who has been making films for almost as long as he has been alive, whose Aguirre, The Wrath of God (1971), Nosferatu The Vampyre (1979), Cobra Verde (1987), Grizzly Man (2005), Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans (2009), Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010) are some of the most controversial and outstanding cinematographic creations, was nothing short of perplexing.

I couldn’t help but think of the bravery, resilience, and a mind-boggling sense of risk and confidence required to overcome to move a steamship of 340 tons over a mountain in the jungle (for Fitzcarraldo, in 1982, for which he was awarded the Best Director at Cannes Film Festival)—but we wouldn’t discuss it.

As this year comes to a close, Herzog, unstoppable, takes it by storm: in October the paperback of his memoir, Every Man for Himself and God Against All, came out simultaneously with the audiobook, read by the author himself, of course! The French-translation of the book, Chacun pour soi et Dieu contre tous, is just published by Les Éditions Séguier.

And in December, a retrospective of his films will be shown at the Pompidou Center in Paris. One thing is crystal clear: no matter what he does, no matter how he does it, Werner Herzog is a man of stories, he lives and tells them with intensity.

*

Ayşegül Sert: I noticed there is a “formula” you repeatedly use in your conversations, including the conversation last night you had on stage at La Maison de La Poésie: “Films are my voyage, and writing is home.”

Werner Herzog: Please be more precise. Yes, I say that, but last night I also said that my prose will have a longer life than my films.

AS: How come?

WH: I know it. And that’s enough.

AS: You feel it? Is that what you mean?

WH: No, I know it. Feeling is something different.

AS: You began by writing poetry at a very young age. Films, and screenwriting, followed.

WH: I did not know that cinema existed until I was eleven. But I started to write before I made my films. At age eighteen, I had two and a half kilos of text. My first film was when I was nineteen. I write my own scripts.

AS: What is it about writing that transcends any other art form then?

WH: It does not “transcend.” It simply is another form of storytelling. It’s probably more—how can I explain it—it’s probably more direct than when you make a film. So many things are in-between in cinema, so many things are between you and the end result—finances, organization, filming, editing, the psychology of actors—it’s a whole amount of steps. But when you write, it’s just pure writing.

AS: Your book ends in the middle of a sentence and without any final punctuation. What was your process there?

WH: When I write, I do not make big plans, I have the text in me. When I wrote my memoir, it’s just my life, so it comes easily to me, I don’t have to invent anything.

And I don’t care where I write—I can write on a noisy bus with my football team drunk chanting obscenities around me, or when I have the time for it, or when I have to do my tax returns then I quickly write ten pages which is three to four hours, or before I have to go to the pharmacy…

When I write, I do not make big plans, I have the text in me.

And the next day I write another ten pages. But of course, it’s based on my memory, and memories are deceiving, you shape your own memories.

AS: In the book you quote the French novelist André Gide: “I alter facts in such a way that they resemble truth more than reality.” And you also mention Shakespeare: “The most truthful poetry is the feigning. Do you mean that writers can never perfectly record the experiences and emotions of their past because one’s own memories is wired to fail them?

WH: Whoever tells you he/she/it knows what the truth is, is not worth listening to. I quote Gide because he gives clear guidance on how we can deal with facts and with truth. And it’s a very significant thing to say. History is a construct of perspectives. Memories in a way are constructed too; you start to modify your memory and actually it is good that we can do that otherwise life would not be bearable.

There is one thing which struck me when I made my documentary [in 2016 Lo and Behold: Reveries of the Connected World—about the internet, the brain, and artificial intelligence], and that is what one of the most famous brain researchers told me in a single sentence and he has an argument of course with scientific tests and proofs to back it up. He said: “There is no truth in the human brain.”

AS: Does that mean that writing a memoir is seeking a truth that can never be attained?

WH: Let’s face it, we do not know what the truth is. It took me much longer fact-checking after I had written my book than writing it. There is no single stone unturned here! And sometimes I had conflicting memories….

AS: Right, and you write on that:

In the labyrinth of memories, I often ask myself how much they are in flux, what mattered when, and how much has evaporated or changed tonality. How true are our memories? The question of truth has preoccupied me in all my films. Today it has even more urgency for all of us because we leave traces on the internet that take on a life of their own.

WH: My brothers [Till and Lucki] read the manuscript. Sometimes they had different memories of the same event, not very much diverging but different versions of it, and quite often I modified my text if both of them were unanimous about the fact that I was partially wrong.

AS: Your answer to young people who come to you for advice on how to make films and on how to write is in two parts—you tell them to walk, because the world reveals itself to those who travel on foot you say, and you tell them to “read, read, and read!”

WH: For me, Virgil’s Georgics is arguably the greatest poem ever written; it’s long, it’s about agriculture and life in the countryside, and he knows about it because he grew up in a farm in northern Italy, and what is astonishing about him is that he is never really descriptive but he names the glory of the beehive and of the apple trees, he names the horror of the plague invading.

Hölderlin, the German poet, is another great one. Montaigne is a wonderful writer too. Or the Chinese poetry of the eighth and ninth centuries. And the fourteenth-century Persian poet Hafez. And Hemingway, I mean mostly his short stories hold a very dense power of prose. And Joseph Conrad!

I could rattle on; I could name you another fifty or a hundred authors to read. [Herzog almost always carries Luther’s 1545 translation of the Bible with him to shoots].

AS: You speak several languages, but you write mainly in your native German. When your books get translated do you read the manuscripts in translation and make suggestions before it goes to print?

WH: Yes, but my knowledge of languages is limited, maybe eight or nine languages, and two of them are not spoken anymore [Latin and Ancient Greek]. I do look into the translation into Spanish and French. For the English translation, I have done a few hundred suggestions.

In one of the previous books [Conquest of the Useless] I sent over two thousand modifications from German to English when I checked the translation. I do not know how the translation into Mandarin or Armenian or Lithuanian is. You have to let it happen, you don’t have to look into everything.

AS: You have seen many places, periods, and political shifts. Would you say that history repeats itself?

WH: That would be a shallow way of seeing things. If you look back in history, previous centuries were uglier and more violent than today, the difference is that today there are atomic weapons which is a threshold and people have become oblivious and forgetful of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. They are like sleepwalkers, dangerously walking into a disaster, and you see that similar kind of frenzy of wanting a war.

One of the best examples is the First World War, everybody wanted it—the Germans, the French, the Brits, everyone in a way. The young recruits were leaving in the trains and the girls were throwing flowers at them and the bishops were blessing them and in jubilation they went to the fronts and within a week came one of the biggest shocks for the human race ever: The battle of Verdun, the battle of Somme….

The second thing that is new, not only atomic wars, but we have the beginning of artificial intelligence, it is astonishing the possibilities, but we are very close to having let’s say thousands of drones—entire clouds of drones—that interact with each other, quickly coordinating which one is to take which target, autonomously, and eventually taking their own decisions, whether to attack or not to, and of course that is something dangerous and that is fast-evolving.

AS: George Orwell in Why I Write:

From a very early age, perhaps the age of five or six, I knew that when I grew up, I should be a writer. Between the ages of about seventeen and twenty-four I tried to abandon this idea, but I did so with the consciousness that I was outraging my true nature and that sooner or later I should have to settle down and write books.

What is your motivation for writing?

WH: I never read Orwell. Writing is not for me to understand. Writing is for the joy of storytelling.

People think that cinema has power, no, it does not. Real power comes from two things: speakers, who have microphones, the great orators. And the other is rifles, weapons. That’s what changes the world.

Books yes, to some degree, because they help form perspectives, but we should not overrate the naked power of writing. It’s better that books just become part of your inner landscape, let’s leave it at that.

We should not overrate the naked power of writing. It’s better that books just become part of your inner landscape.

AS: What’s next for Werner Herzog?

WH: I am writing a new book and working on two other projects —a documentary and a feature film.

AS: Not bad for an eighty-two-year-old who writes in his memoir:

I was deeply convinced that I wouldn’t live to my eighteenth birthday. Once I had safely passed it, it seemed out of the question that I would ever be older than twenty-five. The result was that I began making films of which I could assume they would be all that was left of me.

WH: It happens that there are moments with my films where some people feel almost illuminated, and it’s the same with my books. If they become a companion, that’d be wonderful, and it does happen, I know it.

(This interview has been condensed, and edited for clarity.)

______________________________

Every Man for Himself and God Against All by Werner Herzog is available in English via Penguin and in French via Les Éditions Séguier.